Heather McMordie: Stitch and Stay A While

Heather McMordie

Interview by Crosby Colyer

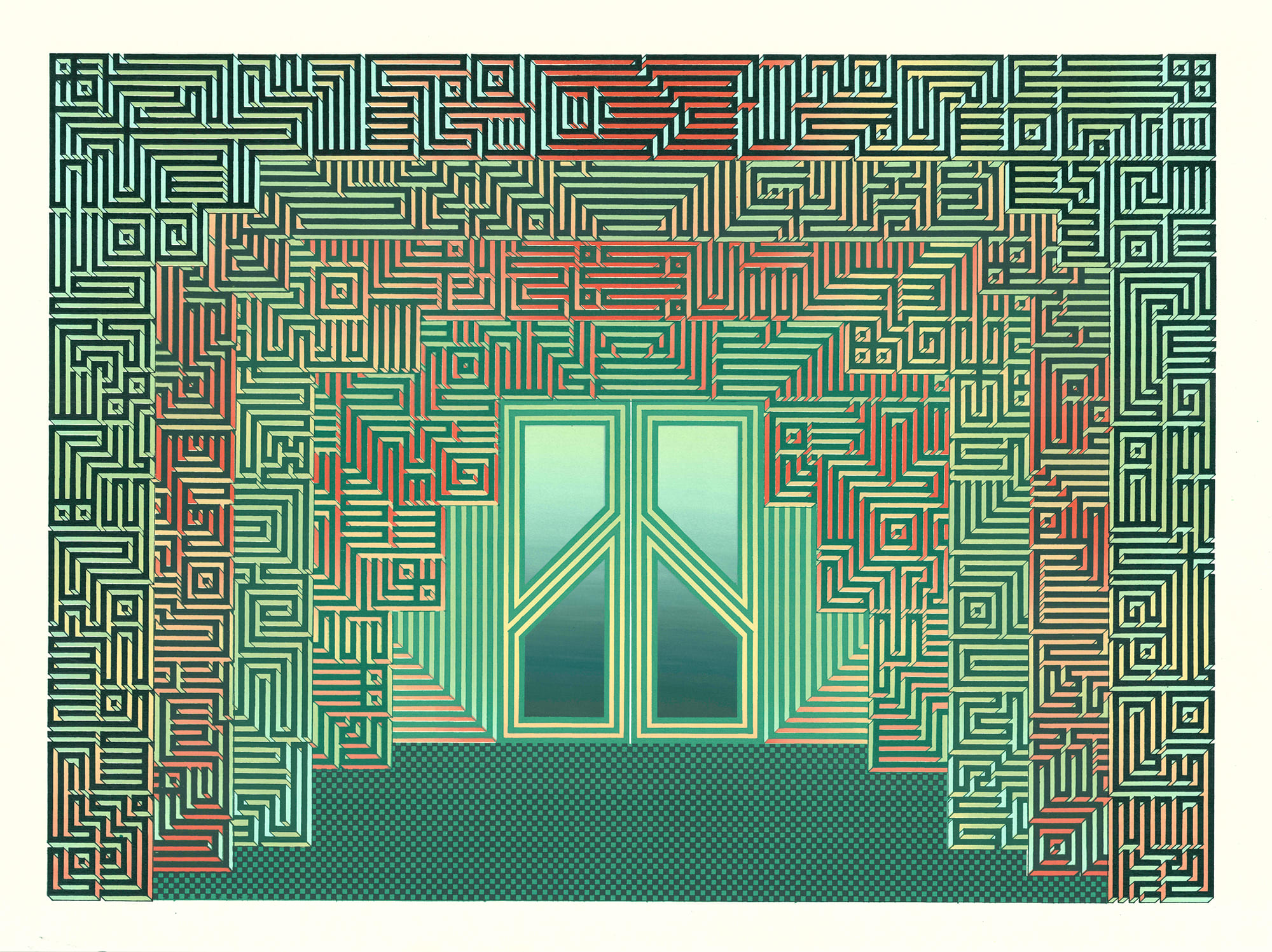

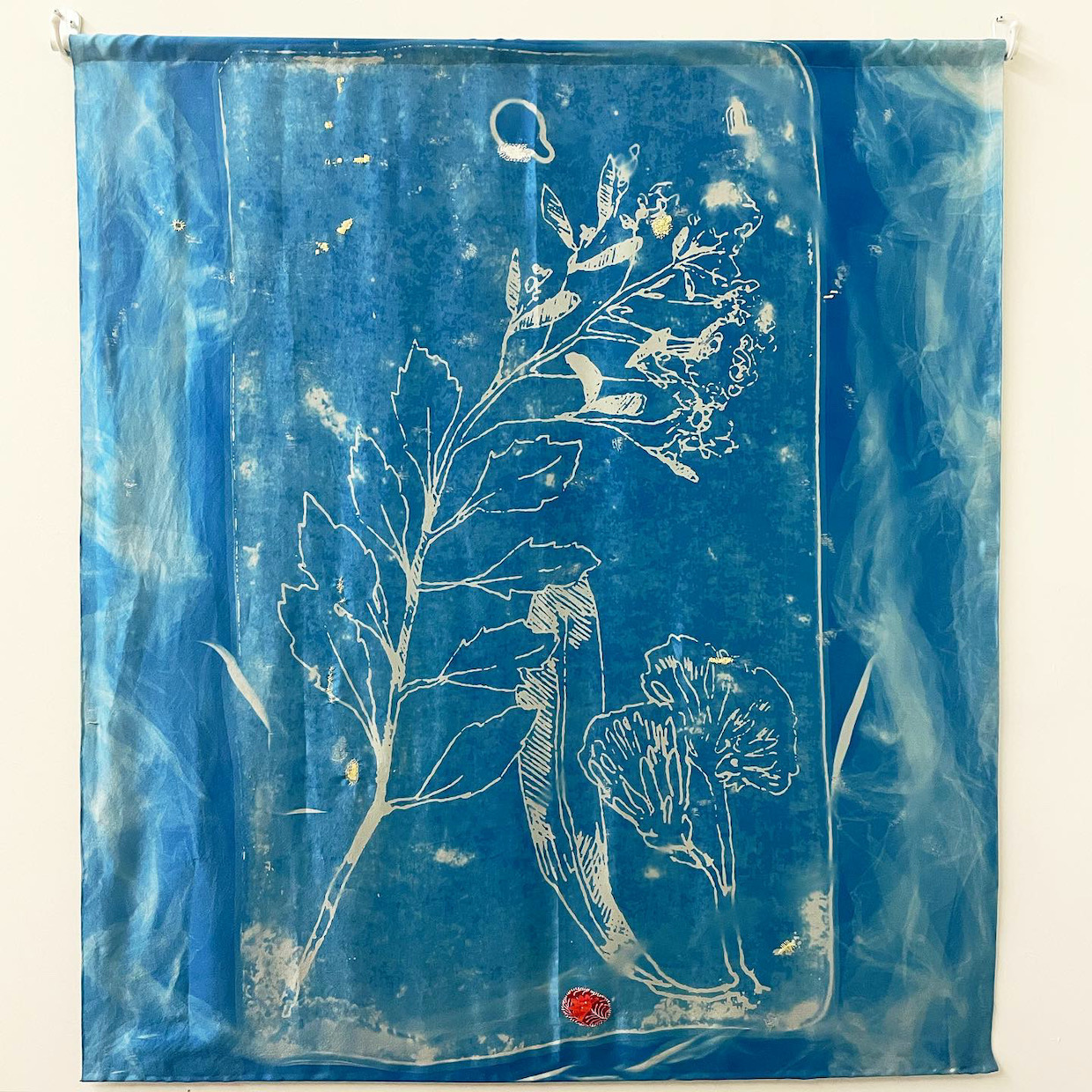

Heather McMordie, Stitch & Stay Awhile: Baccharis Halimifolia, 2021. Ongoing, cyanotype and cotton thread on silk

Providence-based artist Heather McMordie has set out to integrate science into her artwork. Primarily a printmaker, McMordie’s work aims to bring awareness to issues concerning the environment and provide a way for people to spend time in these ecosystems. Her latest project, Stitch & Stay Awhile, involves people from around the country to bring attention to the importance of salt marsh ecosystems. Heather McMordie is the recent recipient of Providence’s Interlace Project Grant with her project “The Providence Community Herbarium,” which is an unofficial survey of Providence vegetation, as seen through the eyes of Providence citizens. The following interview with Heather took place in late October, 2022 as in-person Stitch & Stay Awhile sessions are slated to begin.

Editor’s note: Providence College Galleries is pleased to host McMordie in conjunction with On The Wall: Edie Fake at PCG’s Reilly Gallery, Smith Center for the Arts. Join us to Stitch & Stay Awhile in April 2023! More details coming soon.

Crosby Colyer [CC]: What originally got you into art? How long have you been an artist?

Heather McMordie [HM]: Art has always been a part of my life, but I didn’t always think it would be my career. In high school, I was equally passionate about art and science and was particularly interested in biochemistry. It was challenging to make a choice between the two, but I ultimately decided to pursue art because I thought that it would be easier for me to incorporate science into art than it would incorporate art into science. That goal—integrating science into art—has been a guiding factor in everything I’ve done since then.

I started studying printmaking in 2008 and have been practicing it ever since. My desire to combine art and science is how I found myself in printmaking. The process felt the most experimental and scientific. I appreciated how I could set up a print, almost like an experiment with variables, constants, and a specific research question.

CC: Can you explain a little more about soil systems and why you like to explore them in your art?

HM: My favorite definition of soil comes from a professor’s introduction in the first (and only) soil science class I took back in 2013: “Soil: the excited skin of the earth.” Too often, we conflate the word “dirt” with “soil,” but soil is so much more than dirt. Soil is alive and active. It contains vast communities of microorganisms, networks of root systems, and pathways for water movement. Soils are dynamic. Organic material interacts with inorganic material in a constant cycle of growth and decay.

To me, soils and prints are puzzles, and printmaking provides the perfect foil for visualizing below-ground complexities. Each soil is the unique product of time, climate, topography, and organic activity on bedrock. Prints result from time, pressure, ink, and my creative energies on a matrix. I can ask similar questions about variables and mark-making potential in both fields. Through layered marks and puzzle pieces, the works I make encourage viewers to stoop down, explore, and consider the history of marks at their feet.

Heather McMordie, Puzzling, 2018, screenprint on laser cut paper, 40 in x 120 in.

I am not a soil scientist. I don’t have the same language and tools that someone in the sciences does to talk about, study, and understand soils. I can, however, understand soils through my own artistic lens—through color, texture, sound, and materiality—and create experiences that may allow viewers to set into a deeper understanding and appreciation of soils as well.

In an interview recorded in Field to Palette: Dialogues on Soil and Art in the Anthropocene (ed. Alexandra Toland, 2019), soil scientist Bruce James states, “Soil is challenging to represent as beautiful without a refined knowledge of its inherent qualities.” As someone who sees soil as beautiful, alive, and engaging, that statement has motivated my work. With each project, I strive to bridge the perceived obliqueness of the science of soils and the joy of experiencing soil.

CC: What intrigues you about Rhode Island’s ecosystem that leads to projects about it?

HM: Anywhere I live, there will be something fascinating about the soil and ecosystem that will capture my attention. Urban, rural, and suburban—soil is there and is essential to the communities that live on it.

In Rhode Island, there are many soils and ecosystems I could have focused my research on, but I found myself particularly drawn to the unexpectedness of salt marshes. The first time I stepped onto a salt marsh in May 2019, I was thrown off by the multitude of physical sensations. My feet disappeared into the grass and sunk deeper into the ground than I expected. Water seeped through the mesh of my sneaker. I was inundated with smells (sulfur and saltwater) and sounds (grasses, winds, bird calls, even the constant drone of cars on the not-so-distant roadway). The sheer quantity of physical sensations caused me to move slower on the salt marsh, and in moving slower, I noticed more and asked more questions.

I’ve had the great honor of shadowing researchers in the field and seeing the ecosystem through their lens. I experienced the sights, smells, and bodily sensations of being in the marsh while learning about the marsh system and its functions. Through my experiences with these researchers, I learned how these sensations can all be indicators of marsh health. For example, when out in the marsh during low tide with a restoration ecologist one day, I mentioned that the ground felt particularly mucky and unstable. He then pointed out the “swiss cheese” texture of the soil at the marsh edge. Stooping down, I could see the soil layer suspended with roots dangling down, not quite reaching the sand below. He explained how increased urbanization is essentially fencing marshes into rising sea levels, leaving them nowhere to migrate.

Heather McMordie, Detail: Stitch & Stay Awhile, 2021 - Ongoing, cyanotype and cotton thread on silk.

This visual of marsh degradation and the idea of marsh migration have guided my work in the past few years. Salt marshes provide our communities with many ecosystem services—filtering pollutants, providing coastal buffers, offering habitats, and storing carbon. Healthy salt marshes are essential to our communities’ health and deserve our care.

CC: Stitch and Stay Awhile is a collaborative mending project/art performance that has been ongoing since Covid; what brought about this idea?

HM: Stitch & Stay Awhile was inspired by the laborious and time-consuming nature of environmental care and restoration, especially salt marsh restoration. I had the idea for the project in February 2020 and had initially wanted to create a textile installation that people could mend together. Then COVID happened. I wasn’t sure if there would be a time again when we could safely and comfortably mend together, but that didn’t mean that the need for care and mending had ceased.

I saw this as an opportunity to build community and time for rest in our isolation, so I launched Stitch & Stay Awhile as a remote project. I sent mending kits and hand-printed textiles on damaged silk to participants across the country. The fabrics depicted images of critical native plant species and are 4 ft x 5ft. (Image 4). I asked participants to spend an hour mending while meditating on one of the six field recordings I provided. The mending needed is more than anyone could handle, and participating takes humility and trust that the next person will treat this material with the same care as you. During the remote portion of this project, over 30 people from 11 different states participated. Some had never seen or heard of salt marshes before, and I was pleased to spread knowledge about the ecosystem.

In Spring 2022, I transitioned the project to an in-person format. My focus now is on the people and communities that live near and have the potential to impact salt marsh ecosystems. The in-person mending events are an opportunity to sit together, listen to the marsh (and to one another), build community, and consider our role in protecting marsh ecosystems.

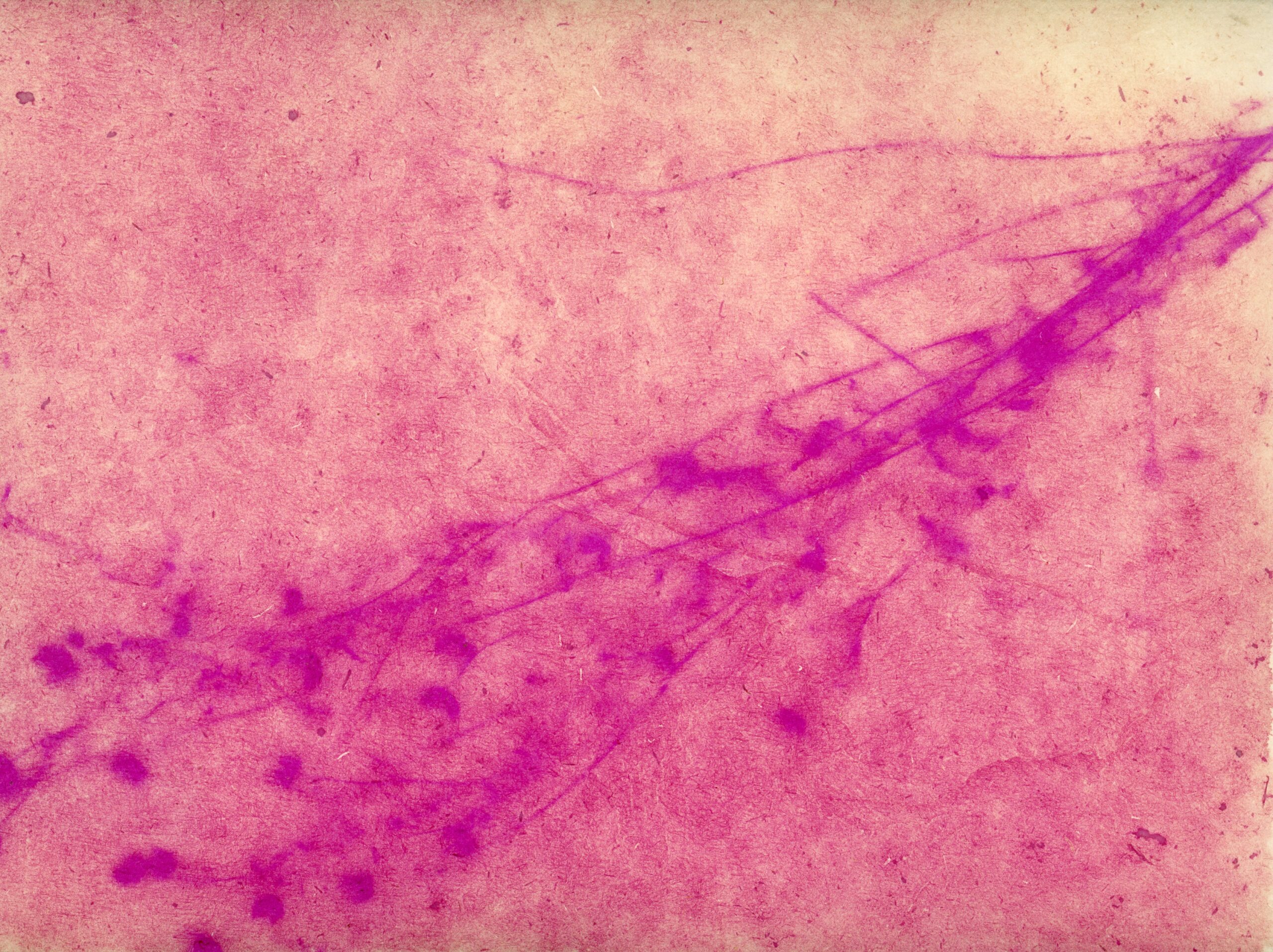

Participant Image: Stitch & Stay Awhile, 2021 - Ongoing, cyanotype and cotton thread on silk; Image Credit: Emily McMordie

What applications does the project have to people looking to be more sustainable with their clothing?

Conversations about sustainable fashion and lifestyle practices have been a pleasantly unexpected byproduct of this project. Participating in the project provides people with three simple mending techniques. While Stitch & Stay Awhile asks you to mend a piece of fabric I’ve created, the skills used to repair them can be applied to the items within your home. Several participants contacted me to share images of clothes and textiles they’ve since mended with the at-home kits I provided.

I think it’s also important to state that this project is about more than just mending textiles. It’s about building a practice of care and repair. It’s about developing value systems that prompt us to move first to repair before simply replacing something. There are so many opportunities for mending in our lives. To mend well, you must first pay attention to the material and get to know its characteristics and history so that you can take the proper approach. This act of paying attention is partly why I ask participants to listen to a soundtrack of marsh sounds while mending. If salt marshes are an area that needs our attention, care, and repair, how can we learn how to better care for them? We can start with listening.

Why do you think that salt marshes are important to bring awareness to and work to protect?

There are so many reasons! Salt marshes provide essential ecosystem services to coastal communities. They filter pollutants, act as a buffer to the ocean, store large amounts of carbon (in healthy salt marshes) and provide habitats to specialized plant and animal species. One endangered species, the Salt Marsh Sparrow, hasn’t adapted to changing ecosystems and is of particular concern. Organizations like the Salt Marsh Sparrow Research Initiative are doing great work to track these populations.

Why do you choose to focus your work on climate change?

I didn’t initially set out to make work about climate change. I was primarily interested in soil, but the more I learned about soil, the more I realized that you can’t talk about soil health without talking about climate change. No matter where you are on the planet, the health of the soil impacts food and energy systems, the filtration of pollutants, and carbon sequestration…all of which, in turn, impacts climate change.

Collaborating with soil scientists in my work has made me aware that successful climate change requires a multidisciplinary approach. In my work with organizations like Creature Conserve or the Urban Soil Institute, I am constantly inspired by other artists, scientists, writers, designers, and creatives striving to make environmental and climate science more accessible to all.

In my work, I have benefitted from the knowledge and generosity of researchers and the ability to physically spend time on these marshes; however, not everyone has the time, inclination, or means to experience a salt marsh (or any ecosystem) in such a hands-on way. It is here that art plays a valuable role in translating the on-site experiences, sensations, and subsequent knowledge into in-gallery explorations. At this point in the climate crisis, it is not enough to generate an emotional response (although an emotional response is inherently part of the experience of place); we also need to encourage further inquiry into these systems.

Participate Image, Stitch & Stay Awhile mending event at Central Contemporary Arts, Providence, RI; August 2022.