Editor’s Note: What is this doing here?

Liz Maynard, PAL managing editor

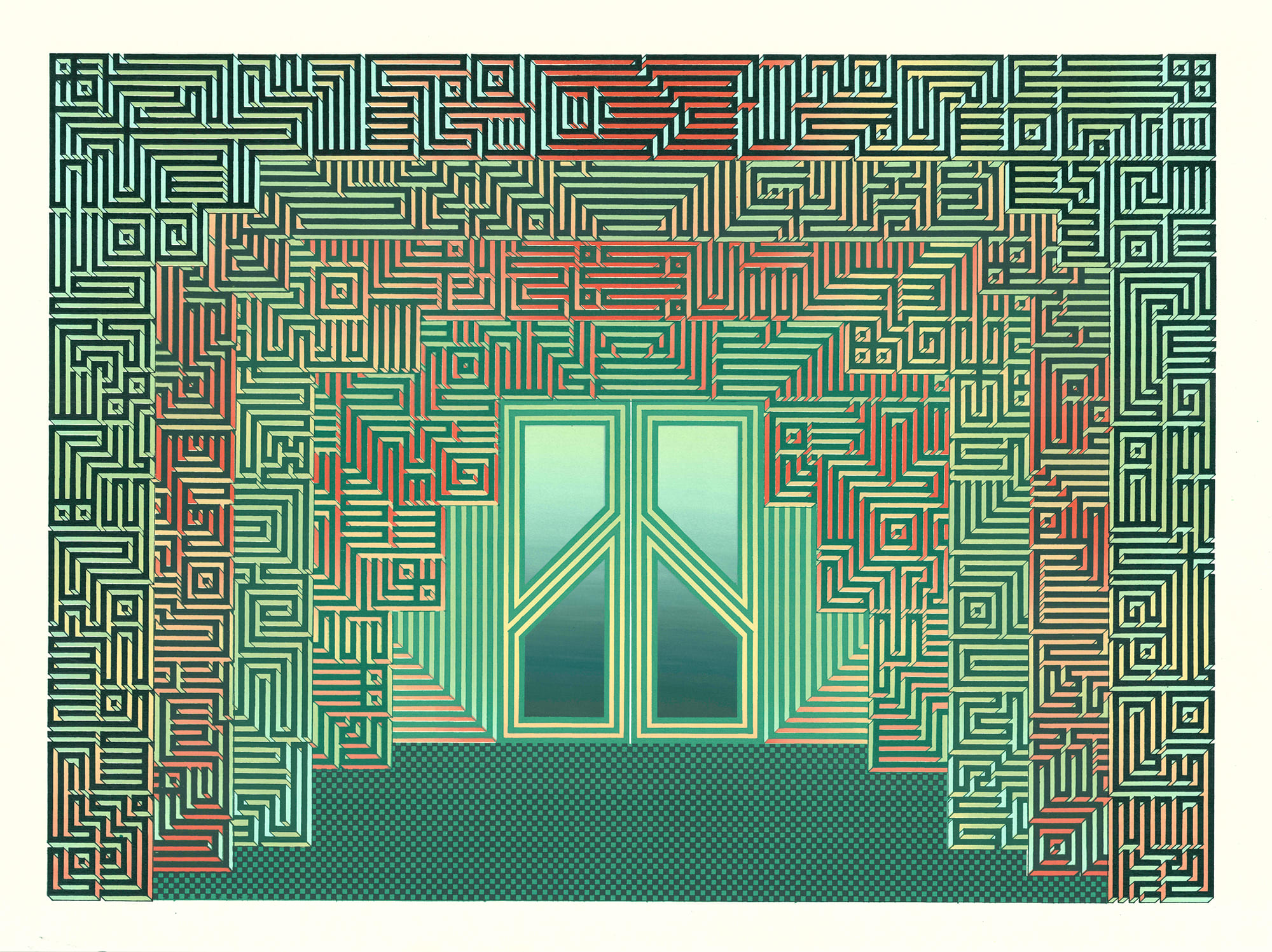

Edie Fake, Processing Department, 2016.

Edie Fake’s Processing Department (2016), featured in Providence College Galleries’ “Past is Present Tense: New Artwork Inspired by Historical Images and Ideas,” is located in the top floor of the Ruane Center of the Humanities. In the midst of the hall’s cream walls with their beautiful wood molding, the acid-colored palette of a sci-fi universe and the linear patterns reminiscent of Mesoamerican gylphs and ornament offer an unexpected portal to a world that is both of and outside Ruane; standing in front of it is much like waiting at a threshold for some unknown process to unfurl. By constructing a fantastical architecture of intentionally complex maps of unknown terrain, Fake’s work invites us on a “labyrinthian journey towards an illusory destination.”

Recently it was my pleasure to read Providence-based writer Susan Solomon’s chapter for a forthcoming volume on James Joyce’s Ulysses. She took the beautiful (and rather meta) tactic of exploring artist Doug Aitken’s architectural installation Acid Modernism. Acid Modernism refers to more than just Aitken’s home: it encompasses both the Sonic and Light Houses on site, and the short film about the spaces. Solomon takes on both in her text, which also explores a truly trippy Instagram post about the house and Joyce’s iconic novel—her exploration is broad but her locus fixed. Her text hinges on Aitken’s use of a simulacrum of the novel Ulysses as a doorhandle to a secret room. The painted wood block is unreadable but literally a portal to another world (though Aitken’s destination is less illusory than Fake’s: the guest house bathroom..!). Solomon’s writing wanders through the house, the film, her own ruminations on the materiality of writing and reading, just as Bloom and Dedalus wander through Joyce’s novel, and Odysseus through the ancient Mediterranean. Her second subsection is titled “what is this doing here?” and I find it’s a phrase that I cannot put down.1

“What is this doing here?” might read like a justification of her approach as much as a query, but I keep returning to it as a kind of invitation to curiosity. As we begin this new endeavor of Providence Arts & Letters, keeping curiosity at the heart seems like a great place to start. We at Providence College Galleries are tasked with the adventure of shaping something brand new, which opens up all kinds of possibilities for how we want to think about and engage cultural production. What exists in PCG’s collection of art objects? What stories do they tell, and how do they evoke the past or offer insight to the future? What does art collection look like in the here and now? How does the past of PCG’s collection inform its new exhibitions? How do its curatorial programs, like “On the Wall,” and “My HomeCourt,” broaden our expectations of the gallery space: as a portal, perhaps?2 How does contemporary art (visual and otherwise) invite us on such labyrinthine journeys that both spiral towards and away from the resources and intellectual inquiries of the College’s beloved community? How do PCG and Providence College sit within the larger frame of the Creative Capital of Rhode Island? And what rich exchanges between place and space can we highlight?

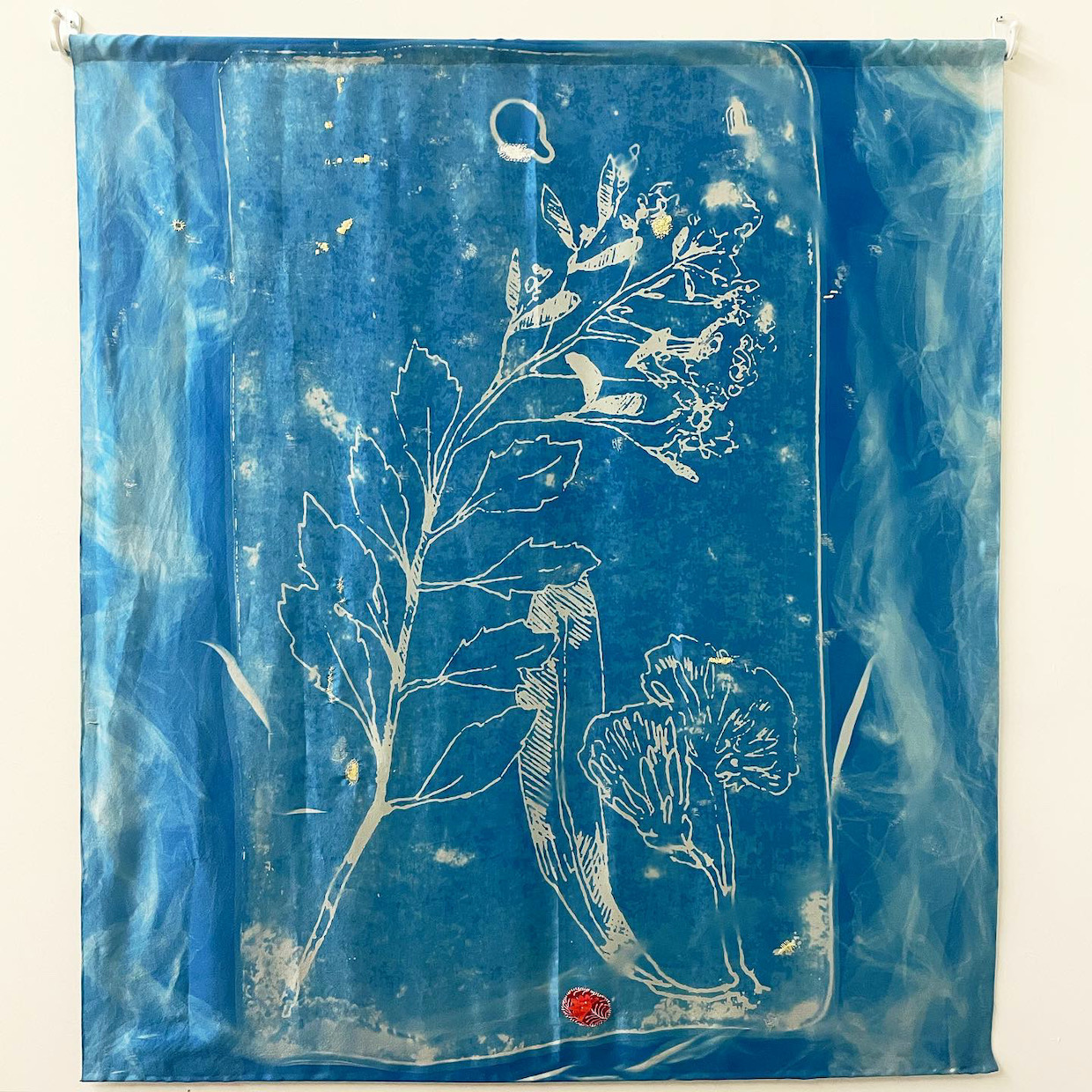

On The Wall: Sheida Soleimani, Installation view.

As an art historian, I was taught to always start with the object. Start with form, the bedrock of formal analysis: shape, texture, line, color, all the ways in which the artwork is sensorily knowable in the world. From there, we can ask that exciting question of “what is this doing here?” How was it made? Under what circumstances? What multitude of conversations is it participating in, be they aesthetic, social, economic, scientific? What portals does it open up? In this way, works of art are like the secret doorhandle in Aitken’s house: they are both their own object as well as a way in. The breadth and depth of conversations that can unfold from a single point of inquiry feel like a grand root structure, very much like Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari’s description of their ontology based on the rhizome.

A rhizome is not a centralized root system that feeds a single organism, like an oak tree, or even better, a carrot. Rather than a deep tap-root that seems to orient things in a linear, hierarchical way, rhizomatic structures can emerge from and move through a multiplicity of directions, like crab grass, shooting off plants in any new direction.3 It’s the hope that Providence Arts & Letters might illuminate connections in this manner, to get at the “what is this doing here?” of it all.

Perhaps because I was an English major in college, I am a sucker for a metaphor, or the layers of meaning that any given text, object, or experience can accrue. While I went on to study twentieth-century American figural art, I have always had a soft spot for the illuminated manuscripts of the Middle Ages.4 In particular, the sometimes delicate, sometimes crude, often funny, marginalia. So in true rhizomatic fashion, here’s yet another way to think about what we’re doing here.

Jean Pucelle et son atelier, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Marginalia, a noun (with plural agreement), might include notes, commentary, illustrations and other kinds of paratext that are either “incidental or additional” to the main thread.5 The modern academic reincarnation of marginalia might be footnotes—Dear Reader, you may have noticed my indulgence in them—and they too can offer that particular pleasure: tracing not just the shape of one thing, but the myriad (rhizomatic) potentials that expand out from any given object, story, or interview. Marginalia are textual and visual manifestations of Aitken’s Ulysses door handle: portals to new territory, towards new illuminations.

Through the rich community of thinkers and scholars at Providence College (both student and faculty) and beyond, situated in the vibrant and artistic city of Providence, Rhode Island, Providence Art & Letters aims to be such a portal. It is our hope that with each offering at PAL our readers will have some new passage revealed, whether that takes the form of experiencing untrod terrain or a novel route through familiar territory. We aim to highlight connections between the past and present, the local and global, from the interdisciplinary to the interspecies,6 so we can keep curious about what we are doing here.

From your PAL,

Liz Maynard, managing editor

Solomon riffs on Aitken work “What Is This Doing Here?” to explore her chapter’s place in the volume, and the wandering quality of both Ulysses and Aitken’s take on Joyce.

With gracious thanks to Susan Solomon. Read her analysis of Doug Aitken’s video installation Wilderness written for PAL, here.

Of course, even so-called taproots are incredibly complex in their variety and expression. Check out this archive of 1,180 drawings, made over the course of forty years, to illustrate both the visible and subterranean growth of trees as a collaboration between Dr. Erwin Lichtenegger and Dr. Lore Kutschera, leader of Pflanzensoziologisches Institute, at the Wageningen University and Research.

We might point to the thirteenth-century French Bible Moralisée as a luscious example of image on text on image on text, that brings the (medieval) contemporary to bear on the (Biblical) historical, a discourse between image and word that spirals both in and out. Professor Daria Spezzaro’s Spring 2022 students created their own illuminated manuscript illustrations on parchment using traditional materials and methods.

Jean Pucelle’s Book of Hours for Jeanne D’Evreux (1324-28) is both a personal prayer book (used for particular times of the day) that illustrates stories not just from the life of Mary and Christ, but also includes sometimes entertaining or didactic marginalia, like the portrait of Jeanne herself reading diligently in the dropped capital (or initium), or the musicians, jousters, and playing girls around the edges of the page.

Marginalia, Oxford English Dictionary, accessed April 2022.

Click here for a text/image collaboration between Biology Professor Maia Bailey and Providence-based artist and activist Eli Nixon.