Calls from the End of the World

On Doug Aitken's Wilderness

Susan L. Solomon

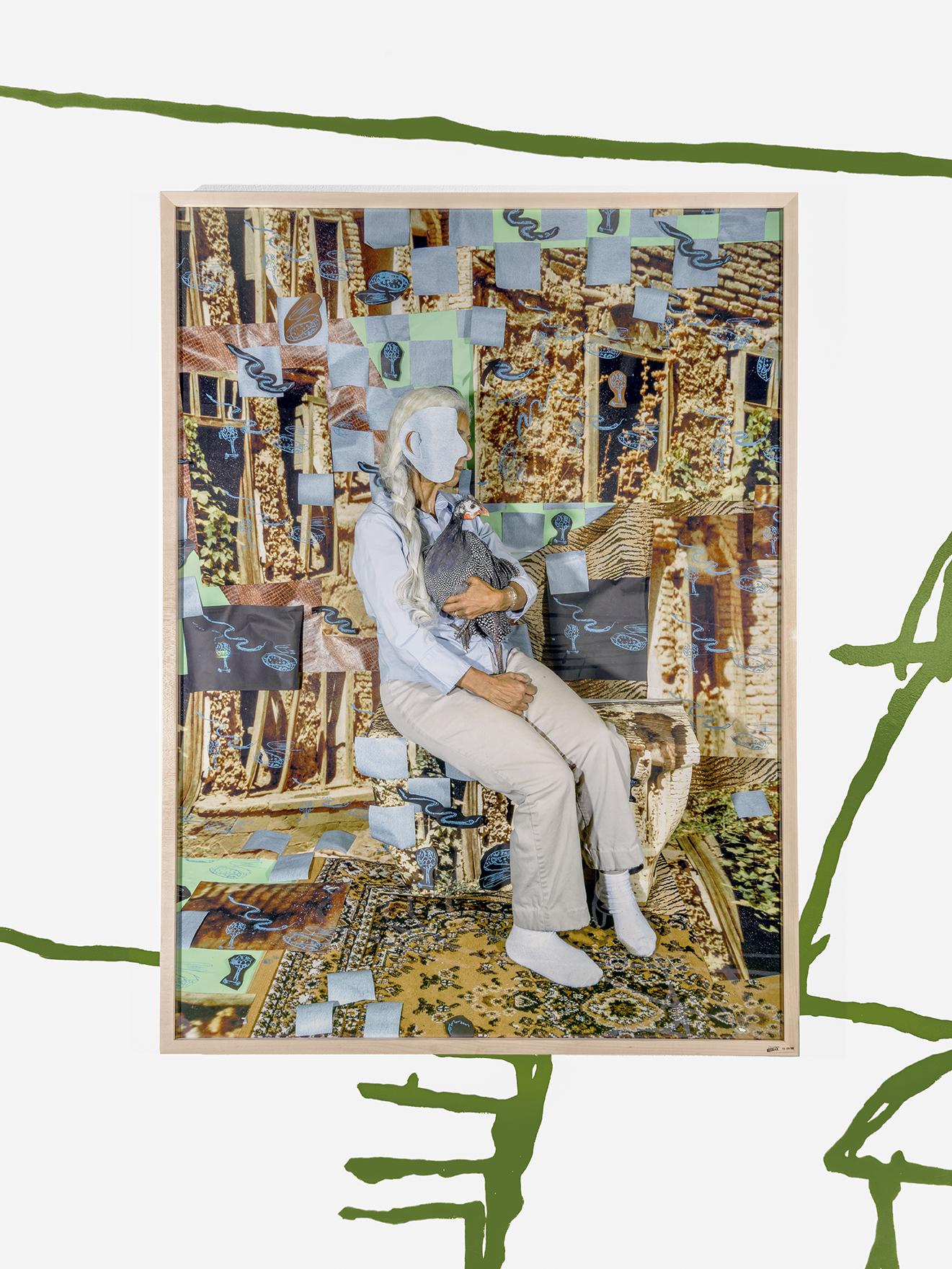

Composited stills from Doug Aitken, Wilderness, 2022, © Doug Aitken, Courtesy of the artist.

I.

If my smartphone can learn my habits well enough to predict what jobs I want to apply to, what countries I want to relocate to, what dresses I might like, and what books I want to read, does it know me better than I do?1 Can it live on without me? Just as it completes my sentences in the emails I compose, can it predict what I might say if my daughters wish they could speak to me after I die?

Maybe my phone could carry on relationships with other phones using algorithms built of our stored thought associations, ruminations, desires, and habits of phrase so that these can live on without us, dehumanizing us past death through the evident predictability of even our most inner lives.

Or will the future look like the social media accounts of an acquaintance of mine? Some of her contacts are unaware she committed suicide from post-partem depression and wish her happy birthday because they see the notification and pause to consider her long enough to send this annual acknowledgment. Facebook could easily have automated this greeting type and spared us the mechanized ritual of keystrokes, but that would be too recognizably meaningless. Then we would enter a scenario in which not only living people unknowingly wish dead people happy birthday, but dead people’s social media accounts wish happy birthday to those of other dead people. Therefore, we are invited to personalize these annual commemorations of our survival, of another orbit around the sun, to mechanically type the same message to different contacts week after week, and then feel a gratitude to Facebook for the reminder that these people exist at all, if they do. In the process, we perpetuate its fiction of relationship and obscure the actual care that lingers behind these transactions.

These are the things I was thinking about in April after visiting Doug Aitken’s solo show, Wilderness, at the 303 Gallery in New York City.2 The exhibit displayed two hung panels, each made of wood and polished stainless steel.3 A sculpture, twilight (triptych), consists of three illuminated works of translucent material molded in the shape of mounted public phones. The show’s central feature was an eponymous video installation depicting people gathered on Venice Beach, California around sunset.4 Many are holding their phones, capturing images or immersed in apps. The sound is a musical composition created by the artist, and the people on camera appear to be singing vocals. However, the actual voices synched to the video are digitally generated. I recollect other images, for example, of people sitting in their cars, headlights on, a gridded collage of suns, another of hands, an overturned bottle of alcohol, and wildfires burning in the hills. One of the Instagram posts introducing this exhibition describes it as a “séance for the future.”5

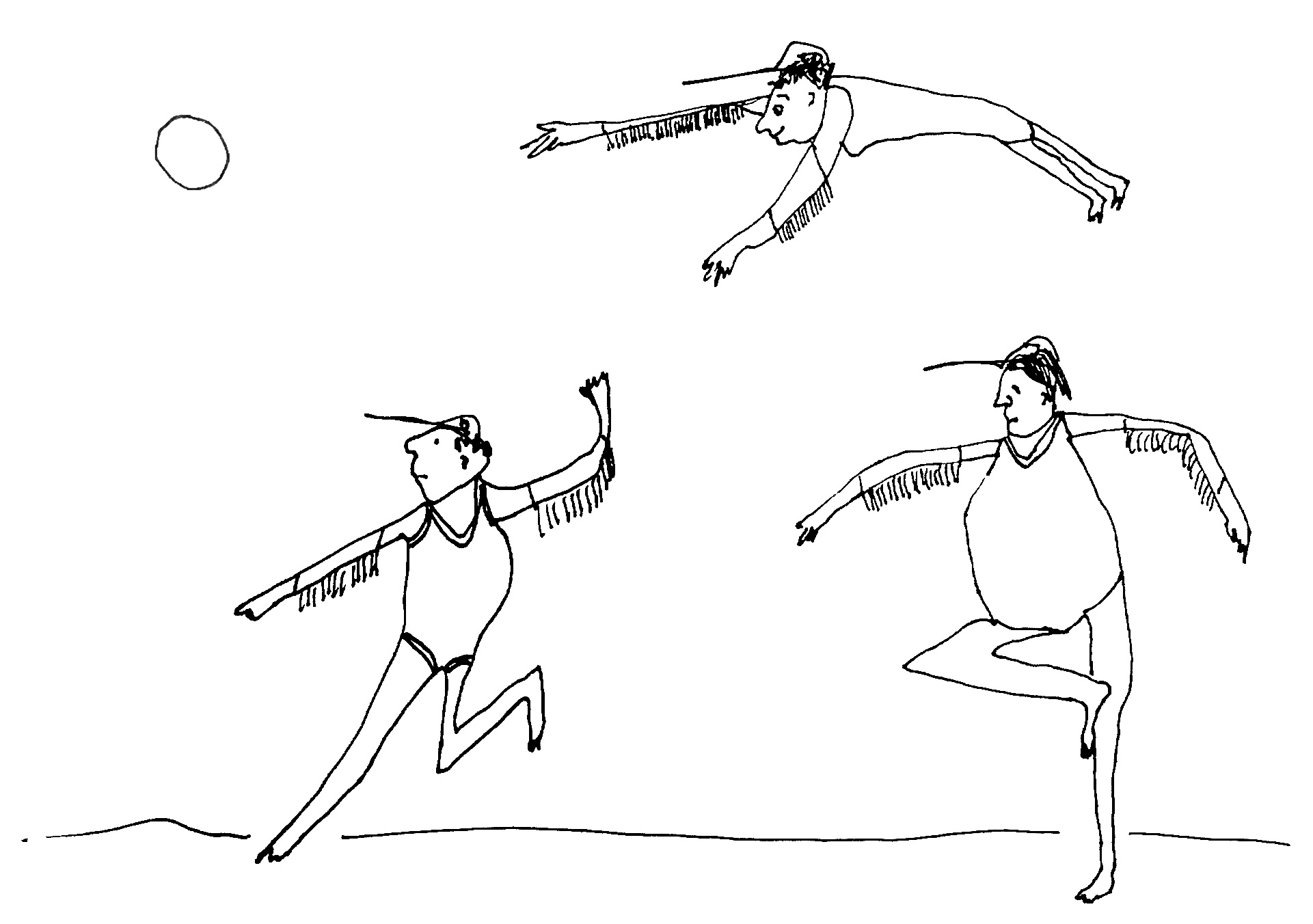

Excerpt of Doug Aitken, Wilderness, 2022, Video installation with eight-channel composited video (color, sound), six projections, four semicircular aluminum and PVC screens. © Doug Aitken, courtesy the artist.

I once visited Venice Beach. A friend had picked me up from LAX and brought me to the fishing pier before going to our hotel. We stood at its end looking at the Pacific, and a pod of dolphins (the first wild ones I’d seen) swam by. They provided shocking comfort after a week of gutting grief. We were there for a service for our friend, who had driven his car off a precipice in one of the parks nearby. After 14 years, I still see him regularly in dreams. I hadn’t answered his last call to me a day or two before he ended his life. Until his account was finally terminated, I called his number daily to hear the recording of his voice on his voicemail greeting. Objectively, this coincidence is meaningless, but subjectively, it is linked to my understanding of Wilderness, itself concerned with the loss of not just one life but the end of life itself, with (dis)connection, missed calls, and this beach at “land’s end.”6

Wilderness’s 14-minute-14-second projection is delivered in a temporal loop onto eight curved screens assembled into a spatial loop broken by four interruptions.7 Its installation in 303 Gallery comprised two opposing screens, each receiving one frame. Perpendicular to these were two more three times as wide, accommodating that many frames. The screens’ circular formation is one of several common features between this work and Aitken’s SONG 1, which premiered almost exactly a decade earlier. The original exhibition of SONG 1 fully enveloped the exterior of the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington D.C.; and the screens assembled for its subsequent indoor views incorporate only one interruption, large enough for spectators to enter a near-circle of screens.8 By contrast, the four visual caesuras built into Wilderness’s screen assembly prevent one from being entirely enveloped in them.9 In both, one can stand outside of the enclosure to view the projection from the exterior faces of the screens. And, if positioned near a gap, one can view a concave screen framed by two convex screens. This configuration of screens in 303 made full use of the privilege of once again encountering art in three-dimensional space.

Installation view of Doug Aitken, Wilderness, 2022, Video installation with eight-channel composited video (color, sound), six projections, four semicircular aluminum and PVC screens. © Doug Aitken, courtesy the artist and 303 Gallery, New York. Photo by Dan Bradica.

II.

Wilderness returns to another feature of SONG 1 by depicting singers, often in intimate close-up shots. SONG 1 delivers the lyrics to “I Only Have Eyes for You” on repeat, voiced by different singers, for around 35 minutes before looping again. Recorded most famously by the Flamingos in 1959 and, according to its Wikipedia entry, more than 20 other artists since it was written in 1934, it holds particular interest for Aitken as a “pop song.”10 In his hands, the cover speaks to the originality inherent in repetition and to the shaping impact of each voice on the content uttered. In terms of the relation between sight and sound, a desolation emerges because most figures sing in isolation and never to a visible love interest. Instead the singers merge together into an indirect relationship of shared experience, embodied through the physical act of vocalizing the same words.

By contrast, the vocalists filmed in Wilderness are un-voiced. As I watch their silenced lips mouth the words dubbed over them, I grieve for the voices withheld in this video. What is more, at times, I feel the repulsion associated with the “uncanny valley” of human simulation. The acoustics spill into my visual perception, leaving me uncertain of the humanity of the faces on screen. Finally, the words “Exit Earth” overtake the triple-wide screens and then disperse into pixelated units, evoking a sci-fi novel carrying that title and the Mars colonization movement so popular in California. Formally, the words recall a scene in SONG 1 in which the letters forming “disappear” fall from a letter board.11

The lyrics in Wilderness are made up of fragmented assertions such as “The sun is going away,” “Out of body, out of mind,” “What will you do? The game keeps changing,” and “You sound so sweet and clear, but you’re not really there. You’re just the sound of the radio.” Instead of summoning the seeming universality of a countlessly covered hit, these words return to the questions of originality and repetition raised by SONG 1 yet with a fracturing ambivalence. I don’t know whether the linguistic commonalities between the verses above and recorded songs that I’ve noted for myself are coincidental, carried out with intention — a Benjaminian “citation without quotation marks” resembling, appropriately, the method of T.S. Eliot’s “Wasteland”— or if they are the unintended result of repeated listenings whereby songs heard become the unconscious basis for one’s own expression.12

Of these, the refrain, “You sound so sweet and clear, but you’re not really there. You’re just the sound of the radio,” is unmistakably adapted from a hit of a similar status as the Flamingos’ recording that grounds SONG 1: “Superstar,” written in 1969 and covered by the Carpenters (1971), Luther Vandross (1983), and many more.13 Its lyrics speak from the perspective of a heartbroken groupie who hears on the radio the “star” with whom she had sex backstage. The retrospective solitude of “you’re not really there” in Wilderness replaces the notion of co-presence expressed by the oft-repeated verse, “you are here and so am I,” sung in SONG 1.

“You” and “I” are indexicals, whose antecedents change depending on the context of who is speaking, to whom, when, and where. When “Superstar” is sung by male vocalists like Luther Vandross or Thurston Moore, the indexicality of the first- and second-person voices enable an obvious role play, an inverted voicing through which the musician sings about himself from the point of view of a female “groupie” listening on the radio. I can imagine that the situation duplicates itself when the fan hears her own sentiment sung back to her in the voice of the star she “fell in love with.” The reversed role of the singing voice to the content and audience is text-book ironic, and so is the verse’s transmission through space and time. This is because the singing “I,” or “you” of the lyrics, actually is “really (t)here” and present at the time they are singing into a microphone. Once their voice is recorded, mediated away from the vocal chords, mouth, and chest that produce these sounds, however, the body is left behind, unattainable, and eventually even dead.

In the context of Wilderness-as-séance, the groupie-to-rockstar relationship is replaced by one between the present and future. The present’s grief for a dead future is caught in a loop, dubbed over, and sung back to it in digital-born, post-human voices. Speaking from beyond both of their graves, the future returns the present’s grieving address to it in disembodied, dehumanized form. Because the intended signifiers of “I” and “you” are less firmly determined in this arrangement, the listener can productively ask who the “you” of “you’re not really there” addresses, especially since so many human figures on screen are not present, but absorbed in their phones.14 Moreover, although their lips move, they are not the ones whose voices are heard. Consequently, this apostrophe might address the humans on screen who only appear to sing, the audience watching them, or the future that becomes increasingly impossible. Perhaps this ambiguity is what connects them. And the comfort is hearing one’s own despair articulated by another.

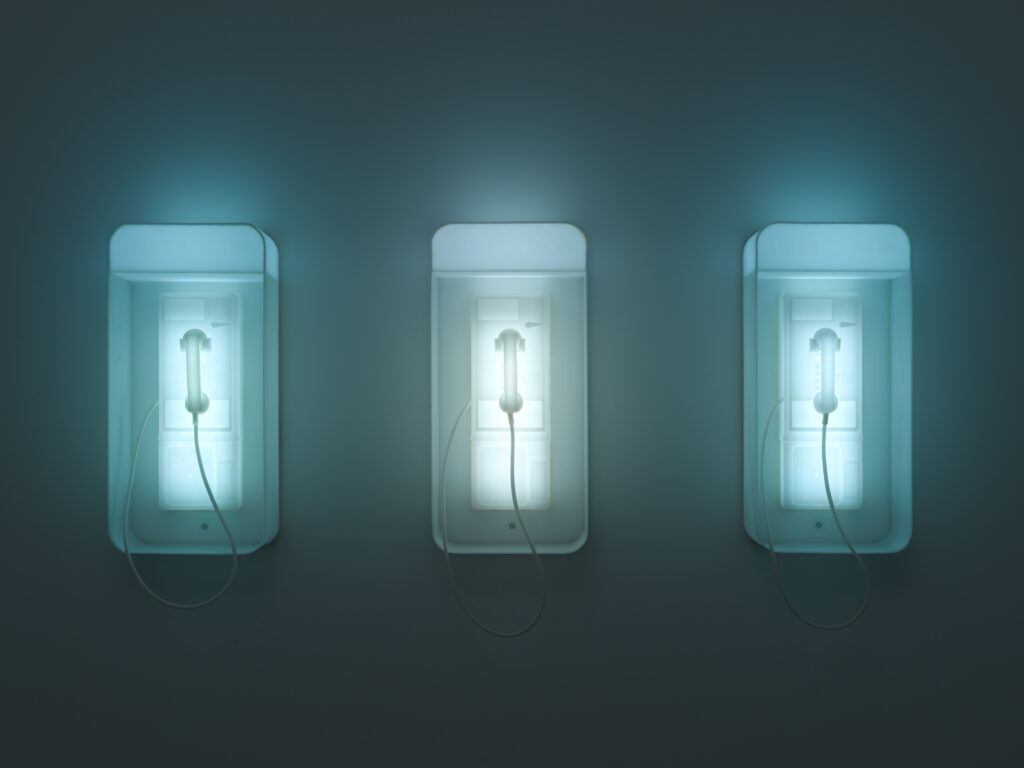

Doug Aitken, twilight (triptych), 2022, Cast resin, acrylic, LEDs. © Doug Aitken, courtesy the artist and 303 Gallery, New York. Photo by Dan Bradica.

III.

Depending on the time of day, the faces of the young people pictured on the beach are shadowed or illuminated by phone screens that pulsate blankly with a unique color, as if expressing a message in indecipherable code. As the sun sets, the people perform the familiar impulse to record the present for the future, in this case, as though they will look back and actually enjoy their crappy iPhone renderings of a spectacular sunset. Metaphorically, they record the present for a posterity that doesn’t exist and miss what actually does.15

Despite the critique leveled at phone dependency by Wilderness, many visitors at the screening—inevitably and unsurprisingly—were using their phones as second-eyes to record and view it in flattened and miniature form, repeating the same action of those on screen and enacting a sort of visual dubbing over of the unfamiliarity of encountering art in “actuality,” which itself somehow demands the use of quotation marks these days. I used my phone too, but held it low—feeling suddenly self-conscious and resentful of my need for this device.

Around the midpoint of the video, each screen breaks into a grid of smaller, regularly repeated and inverted frames, resembling the distribution of color and pattern found in patchwork quilts. This configuration recalls the fabric work Aitken’s workshop began during the pandemic, where geometric shapes and letters were stenciled and cut from “debris” before being stitched together into “flags.” Like collage and film editing, quilting severs, salvages, juxtaposes, and transforms. During this climactic section, the collection of frames projected onto fabric-like screens subtly connotes a connection to quilting’s work of recovery, repair, and protective comfort. Here Wilderness offers a glimpse of hopefulness that something might still be built from the debris of this present.16 Fabric is also associated with the work’s “sound and language” by the exhibit’s press release, which it describes as a “subconscious thread” and “connective tissue.” The latter, an anatomical term, brings to mind on one hand a naturalized social and ecological order in which all things coherently interconnect. On the other hand, the word choice emphasizes the precarity of this interdependent existence, which hangs by a thread, held by fragile tissue.

In a separate space, three illuminated mounted payphone sculptures formed the “triptych” called twilight, but maybe they were also a trio, singing in silent chorus via light signal. I thought they were signaling to one another in a Morse code of their own. In fact, they had been designed to react to visitors’ movements in the room. Assuming I was a witness, not a participant, in their performance, I missed their calls. These memorials to an obsolescent technology of connection had nonetheless acknowledged that I was really there, but only with my own belated recognition.

Many thanks to Elizabeth Maynard, Doug Aitken, Jen Cox, 303 Gallery, and my brother Wyle for their various forms of support with this essay.

Doug Aitken, Wilderness, 303 Gallery, New York City, April 27–May 27, 2022.

One comprises seven iterations of its title, WILDERNESS, in a stencil font resembling Bauer’s Futura. The second is a fractal- or flower-like design called Terra (camouflage). See link in footnote 2 for images.

For a near-complete view of the video, see here.

Doug Aitken Workshop, Instagram Post, “Wilderness – a séance to the future,” April 27, 2022.

303 Gallery Press Release for Doug Aitken, Wilderness, New York City, April 27–May 27, 2022.

Although the video posted to its site is shorter, the record provided by 303 Gallery for the film documents that is 14 minutes, 14 seconds long, thus looping even the numeric digits that measure its length.

For a long video view of SONG 1, see here. For installation views of the Hirshhorn exterior, see here.

See additional screen formations in installation views from the gallery here.

“I Only Have Eyes for You.” Wikipedia. Accessed June 2, 2022.

Doug Aitken, quoted in Geeta Dyal, “Doug Aitken’s Song 1 Wraps Museum in 360-Degree Panoramic Video.” Wired Magazine. April 18, 2012.

This disintegration of lettering relates to the other work called WILDERNESS exhibited in the show, which consists of the text of that title mounted onto a panel and repeated seven times. The three iterations set above and below the legible center line are progressively distorted and elongated the further they are from it. A kind of character development takes place as the word slowly emerges into clarity from the formlessness of the first line and then loops back to that original state by the final one.

The press release actually describes the setting as “appearing as a wasteland.” See footnote 5 for the link to this source.

The corresponding lyrics of “Superstar” are “Your guitar, it sounds so sweet and clear/ But you’re not really here, it’s just the radio.”

See Aitken’s text sculpture You/You (2012), which invites the same question by means of a reverse-inverse spatial loop.

This handling of the smart phone is carried over from Aitken’s Don’t Forget to Breathe (2019), where statues made of translucent glass glow in varying colors and take the form of solitary humans with phones in hand.

When produced to function practically as a blanket, such fabric work salvages in order to comfort and protect human bodies. Interestingly, Aitken’s flags have been employed as apparel by members of LA Dance, so they are employed not only as wall hangings, but to cover the artform of the performing body as well.