Ghostwriting and Rehabilitation: Sheida Soleimani

Interview by

Taylor Maguire (PC '24)

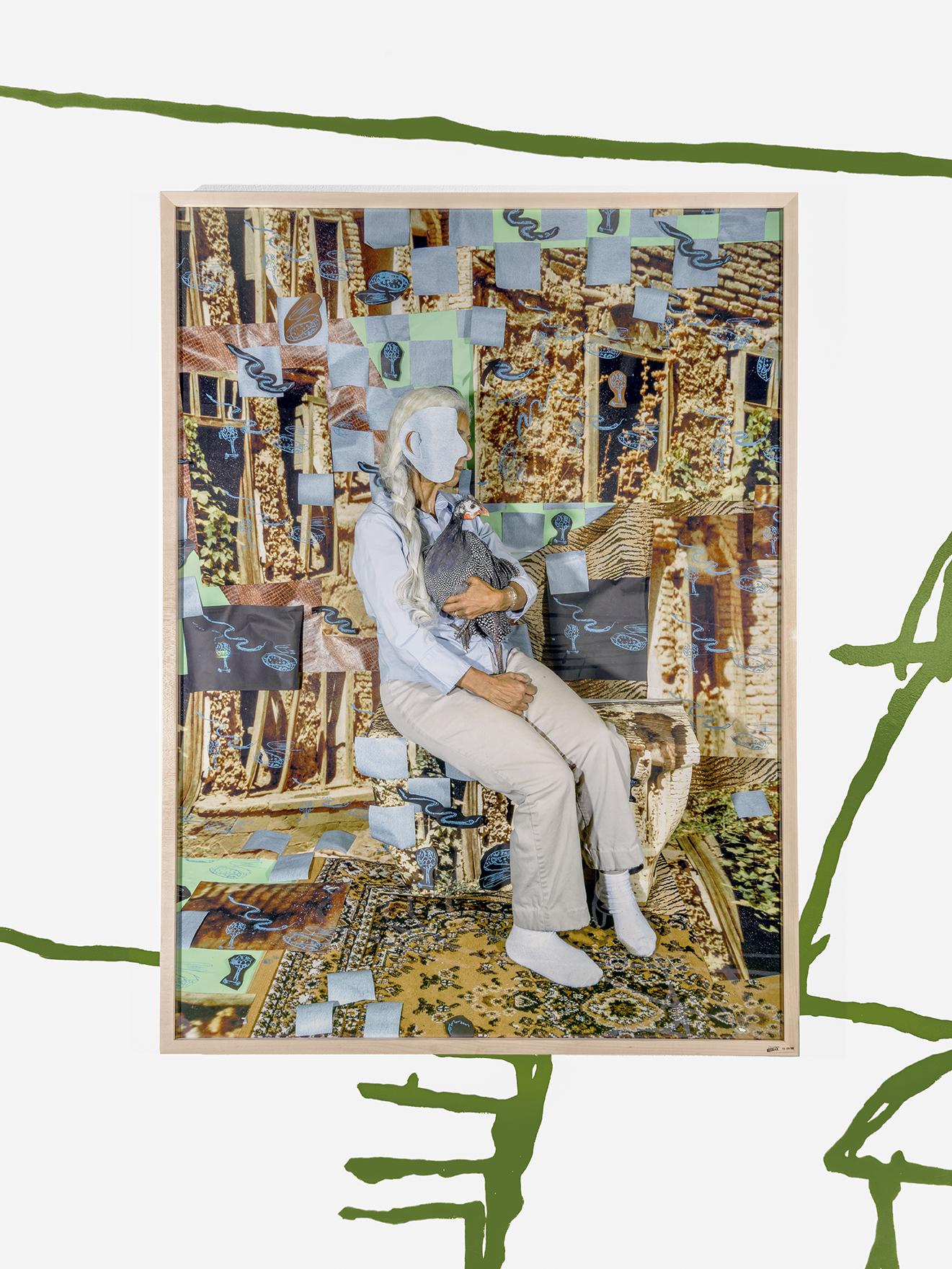

Sheida Soleimani, Noon-o-namak (bread and salt), 2021, Archival pigment print.

In her exhibition, On the Wall: Sheida Soleimani, recently on view at Providence College Galleries, the Providence-based artist takes on the role of ghostwriter by translating her family’s stories of political persecution and survival through the lens of photography, painting, and collage. After attending Soleimani’s artist talk, I was inspired by her empathetic nature and drawn to the ways in which she went about telling the complex stories of her parents through this current Providence College Galleries installation. Soleimani’s ability to weave together the larger socio-political issues and emotional experiences of her family within the intimate environment of the installation creates a unique opportunity for viewers to engage with these complex issues. Soleimani’s current body of work is a chance for both her and her parents to reflect upon and perhaps release the baggage they have been collaboratively carrying.

I was excited to have the recent opportunity to sit down and speak with Soleimani in her exhibition to discover more about her life and interests, which often converge in her artistic practice.

TM: What was the most challenging part about making this exhibition,On the Wall: Sheida Soleimani?

SS: The hardest part for me was the emotional aspect of it. I mean, there’s the ethical aspect in photography, of how you as a photographer portray bodies and how you as a viewer look at images of people, which can’t help but be through the lens of biased societal conditioning. I was afraid of subjecting my parents to that because it’s not like I can erase the conventions of photography, but I wanted to try to restructure that relationship between photographer/viewer and subject. I tried to essentially subvert the gaze of photographer/viewer by allowing my parents to mask, to cover their faces. Not only did it protect their identities, but I felt it allowed them to maintain their humanity in all its fullness, with opacity.

The hardest part really was that there was so much that my parents have told me growing up but there’s also so much that I apparently didn’t know. For instance, in the image where my mother holds the bird, we see her reaching through a shredded, pixelated photo of a prison called Khoy, where she was kept in solitary confinement for almost a year. My mother had told me a bit about the prison and her time there, mainly that she had a window at the very top of the room and although she couldn’t see anyone, she could see the light change through the day, and she could talk to people in the cells around her. But only recently did she tell me about some of the people and conversations, like the story of the woman next to her. Apparently, she had just given birth to a child and she was due to be executed, but they said that they wouldn’t execute her until the child stopped breastfeeding. So, she was trying to breastfeed the child as long as she could, and this child was two and a half, almost three. He stopped breastfeeding on his own and so they executed her. I remember as my mother was telling these stories, she was crying, and I was crying, for all these awful things that she’s been holding to her whole life.

Sheida Soleimani Khoy, 2021. Archival pigment print.

That’s my mom’s handwriting screen-printed onto the photo. It’s a poem she wrote about her being this bird that’s trapped. No one pays attention to her—she’s been forgotten and left in this solitary prison to die. The analogy of a caged bird is something that we hear a lot, but it really resonated with her. In this photo, she’s holding an eastern bluebird that I had just rehabilitated. I learned animal rehabilitation from my mom, so when she came to visit we took this photo and right afterward we went to go release it. After we released it, we both cried. It was really intense, but the symbolism just felt really heavy.

TM: At the exhibition opening, I learned that this was a new body of work that the [Gallery Director and Chief] curator, Jamilee Lacy, had encouraged you to show. I am curious to hear more about the process of shifting this new work into the exhibition parameters of On the Wall, which requires artists to think about the gallery walls as a site for production.

SS: It was weird, I’m not going to lie! Because when Jamilee and I first started talking two years ago we had a totally different show in mind. I knew there had to be a wall aspect, but I didn’t know what it was going to be, just that I would figure it out. I’ve never done a mural before or anything with wall painting. I paint my backdrops, but I thought this wall drawing could become the theater and the stage, just like the sets I build to photograph in my studio. Jamilee really encouraged me to do it, which is great. In November I started making this work with my parents, and I think I saw Jamilee in October and told her about it and about this map my mom drew, and she was like, “Do you think we can do this in this amount of time?” I said, “I don’t know, we’ll see!”

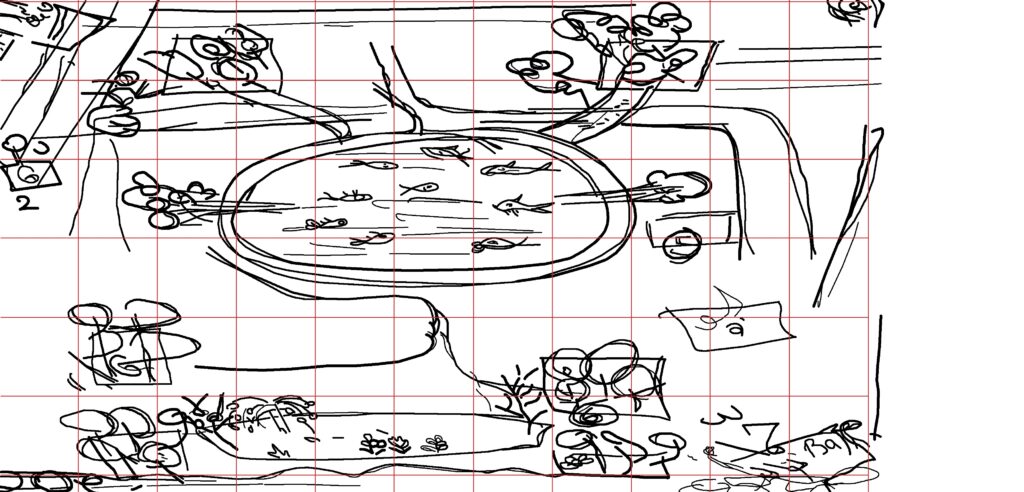

So yeah, my mother made this drawing of the house she grew up in, which is the same home that my father went into hiding in, and a map of where she buried eight babies in jars of formaldehyde under her favorite tree. There are source images that serve as referents for all parts of the map. But yeah, I held onto it for years and I thought this could be an opportunity to put it on the wall.

Sheida Soleimani Preparatory drawing for floor installation, 2021. Commissioned by Providence College

TM: How does it feel standing inside of your mother’s map?

SS: It is really surreal for me because I never got to go to the house, because I am exiled and my parents are exiled, [but] I hear all these stories about it all the time. My mother has created all of these stories to help me remember it but it’s not like I can remember it, because I have never seen it. Being in this space makes me feel like the closest I will ever get to it which is an intense feeling for sure.

TM: How do your parents feel about this exhibition? Is this something you want them to see in person?

SS: I do want them to see the exhibition in person and I have shown them photos of it and they are very excited about it. It was amazing to have them be a part of this work and to be so supportive. They were willing to do it because they want their story to be told. They’re not ready to tell their story themselves, but they always talked about the idea of having a ghostwriter who would tell their story. They wanted to hire one to write a book but that never happened. I wanted to try to take on that role. It is important for me to transcribe their stories and it’s important for them for it to be transcribed, so I feel lucky that they are letting me.

TM: One of your rescue birds is in your work, is this the first time that your practices as an artist and wildlife rehabilitator have converged?

SS: For the most part, yes, over the past few years it has been creeping in. The New York Times had asked me to do a piece on how to have fun during Covid, which I thought was a really fucked up question because I was like, “Well, I’m not sure that’s the angle was should be taking here, but I do agree we can find ways to cope.” I ended up doing a series that were editorial pieces for the Times about coping mechanisms with birds, and that was the first time really that the birds had come into my work and still lifes. It’s been an intense but good feeling to incorporate them as a way to talk about caretaking and vulnerability, because they’re kind of like my built family, right? Like we have our chosen family, biological family, and built family, so I’ve built relationships, some brief and some really deeply embedded in my life now, with all of these animals, and it’s all good connective tissue.

TM: Has there ever been a teacher or professor who has inspired you and your work?

SS: Liz Cohen. She is my artist in residency, not exactly a professor from Cranbrook [Academy of Art], you don’t really have teachers, you have artists who you work closely with. She’s more like my art mom. She’s the reason I teach the way that I do, she’s the reason I think the way that I do. And her family had a very similar story to mine, but her family is from Colombia, not Iran. It’s hard because in undergrad I did and didn’t have professors like that, but in grad school I knew I was looking for someone to work with who would be in this mentorship relationship with me and that’s what happened. And now Liz and I talk on the phone like every other day. She’s my best friend.

TM: Do you ever listen to music while you work? If so, what kind of music is your favorite to listen to?

SS: All the time. I love rap and hip hop. Like love. Like I will be in the studio and the first ten minutes before I even start working, I will just be dancing around. I would say Atlanta Trap, you know crunk from 2001. I like all the 2000s hip hop since I grew up listening to it, and obviously, I like a lot of new stuff too.

TM: If you could meet one artist, dead or alive, who would you want to meet?

SS: Jack Smith from Flaming Creatures.

TM: I know that you are an art educator, if you could teach a class at Providence College what would you want to teach?

SS: I am interested in a conservation class in the future, but I think that one class I am really interested in teaching more of is the ethics of photography. A lot of people think about photography being this easy and free media where they can capture images of whatever they want, but I wish people thought more about what they are taking photos of because they have implications. Photography leaves its subjects particularly vulnerable to stereotyping, because the subject can be viewed but can’t speak for itself—it’s been “captured” by the photographer’s gaze, which exposes and frames the subject. I think the most exciting photography right now is the photographers trying to subvert or reroute that relationship.