Meaning-Making in the Here & Now: Reflections of an Emerging Curator

Melaine Ferdinand-King

Providence Biennial Curatorial Fellow

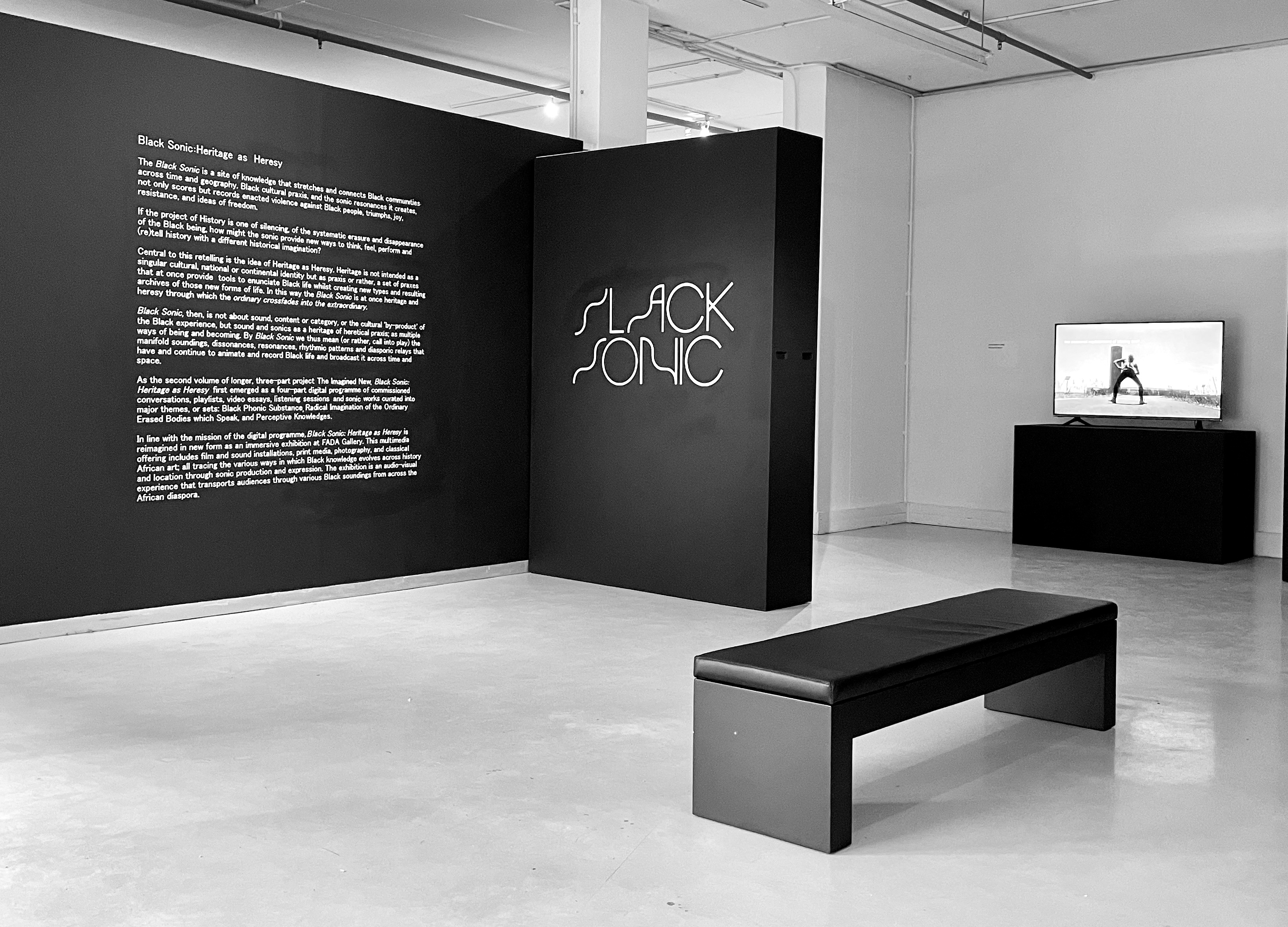

Still from video "Autocorrect" by Jonzi D and Saul Williams, in "Black Sonic: Heritage as Heresy" exhibition curated by Melaine Ferdinand-King, FADA Gallery, University of Johannesburg, South Africa. Courtesy of Melaine Ferdinand-King.

Melaine Ferdinand-King is a fellow in the Providence Biennial’s inaugural mentorship program for emerging curators, Providence Curates. The mentees will explore the theme of “commemoration” in concurrent exhibitions in 2023; PAL invited the curators to reflect on the growing and evolving field of curation as practice.

Growing up in central New Jersey, my grandmother would take me on bus trips to explore Manhattan. By age 13, I had attended Broadway shows, live concerts, and excursions to museums of art, science, and history. Through these NYC visits, it was clear to me that human creativity was vast and potentially infinite – each person had their own story and unique mode of expression. I became an observant girl out of sheer intrigue- I was fascinated by the world around me and the elements of creation. I had never considered becoming a curator professionally, but I paid attention to the nuances of mood, style, and placement, especially watching my grandmother. Nana taught me the importance of “the little things” and the difference a detail could make. She knew how to shop with intention, selecting the perfect jar of apricot jam for family lunches or how to thrift for nice, white tablecloths at a local flea market. I watched her decorate the living room with eccentric pieces she had collected over the years and choose the right color-texture patterns for her daily outfits. Nana gave me my first lessons in arrangement and presentation; I took her course in curation from childhood to my adult years, when I ventured into the fields of sociology and Black studies.

Nigerian archival performance textiles. Installation view, "Black Sonic: Heritage as Heresy" exhibition curated by Melaine Ferdinand-King, FADA Gallery, University of Johannesburg, South Africa. Courtesy of Melaine Ferdinand-King.

In 2018, I entered the Ph.D. program in Africana Studies at Brown University. My previous research explicitly focused on Black women’s worldmaking practices in times of crisis and recovery throughout the African diaspora. Over time, I became more interested in specific questions of representation, interpretation, and translation; how does one assign meaning to symbols, objects, places, and people? How do we understand and express our experience of the world around us? I found many answers to these questions in books on aesthetic theory and cultural criticism. Moreso, I saw language come to life in the local art scene.

Moving from undergraduate studies in Atlanta to Providence after graduation, I was sure New England would be quiet and unassuming. It did not take much time to realize that there is more to Providence than meets the eye. The creative expression of the city revealed itself to me through the people I met – designers, activists, small-business owners, sewists, intellectuals, street prophets, and photographers – people with big ideas and dedicated work ethics. As I developed relationships in my first two years of graduate study, I realized how integral art is to many aspects of the cityscape. The city’s culture is a vibrant melting pot of global customs. In the annual parades, block parties, popular bars, and restaurants, I noticed the intermingling of peoples from Cape Verde to the Dominican Republic, from Accra to Brooklyn. Still an observant girl at heart, I became attuned to sights on the South Side, the bustle of downtown, and the breeze in Fox Point, picking up details and cultural information along the way. Although I hadn’t yet had a formal curatorial practice, I’d been an involved community member through my work in the city and the university. I theorized on aesthetics in public forums, managed arts-based projects, and coordinated social gatherings for members of the Black and brown communities.

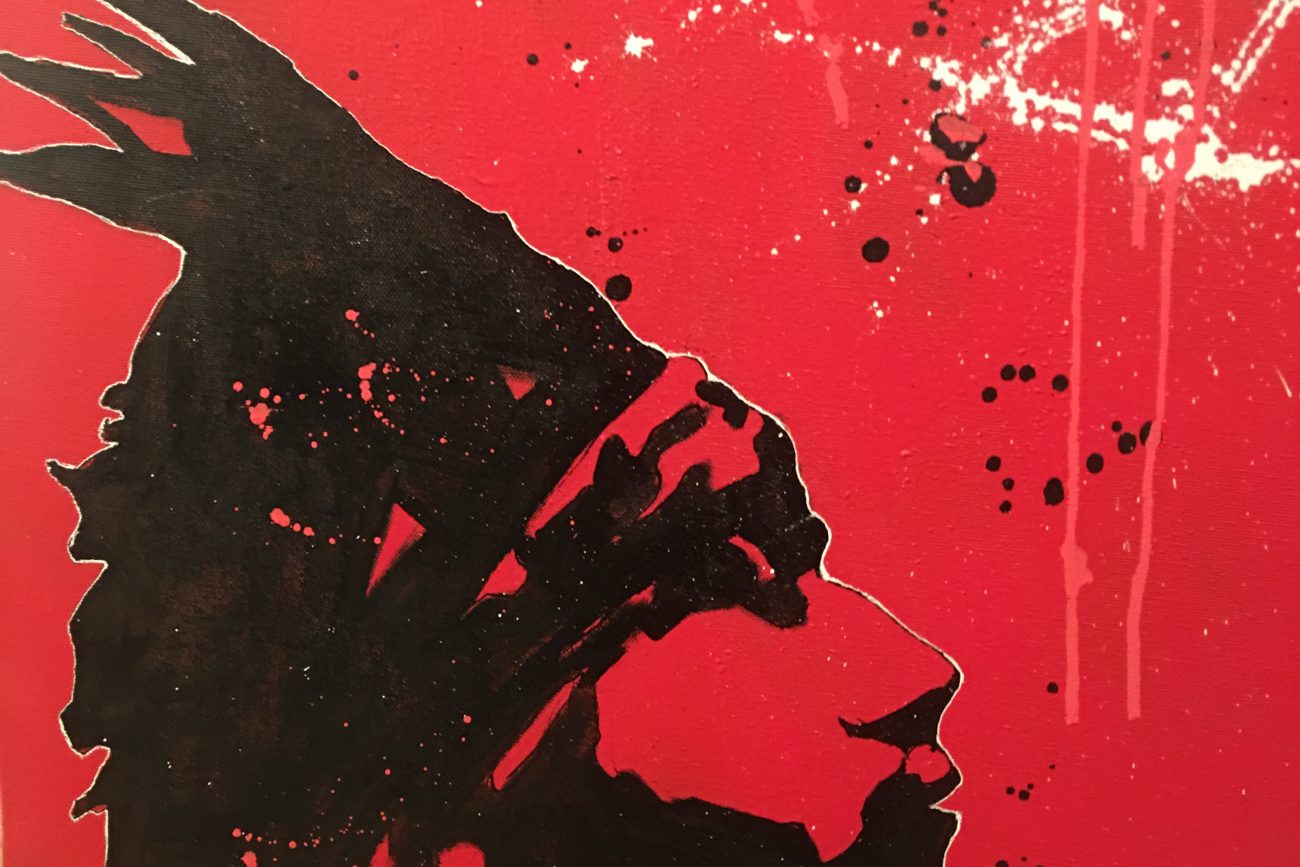

"Kingdom of This World," Edouard Duval-Carrié, in "Black Sonic: Heritage as Heresy" exhibition curated by Melaine Ferdinand-King, FADA Gallery, University of Johannesburg, South Africa. Courtesy of Melaine Ferdinand-King.

I also spoke with friends and colleagues from different backgrounds who admitted they felt uncomfortable in institutionalized cultural spaces like museums and galleries. I met people from Providence whose understanding of art existed in public spaces, like the large building-side murals, colorful graffiti, and organic street fashion. “Art” is still relatively stigmatized, often considered frivolous, or solely associated with upper-class or elite societies. There was a substantial divide in perceptions of the proper place and audience for art in the city.

Motivated by my research on Black consciousness and local organizing work, I was moved to translate theory to the public, coming to curatorial work as a happy medium for reaching new, non-academic audiences. My first formal position as curator was through my work on The Black Biennial’s inaugural exhibition, New Beginnings, from March-April 2022 at the RISD Museum Gelman Gallery. I was accepted as one of two curatorial mentees into the Providence Biennial for Contemporary Art’s Emerging Curators program shortly thereafter. I was, and still am, excited to be amongst other, more experienced, curator-artists who can assist in developing an exhibition as a solo curator. The experience has helped me find the intersection between my formal studies and my work in public arts.

Still from "Waiting for Myself to Appear," Michael McMillan, in "Black Sonic: Heritage as Heresy" exhibition curated by Melaine Ferdinand-King, FADA Gallery, University of Johannesburg, South Africa. Courtesy of Melaine Ferdinand-King.

Curating is both an everyday practice and a serious craft requiring intention and vision. The curator is an active learner and participant in their environment. The crafting of an exhibition is derived from self-education and multiple modes of consumption, predominantly reading, film watching, and community engagement by way of attending cultural or political programming. Curation necessitates a survey of current events and a rigorous assessment of the social climate in which the exhibition takes place. From this assessment, the curator must ask themselves what drives their response to issues and themes they’ve encountered and what messages they want to convey through their unique lens. My personal philosophy underscores the necessity of praxis: we need new, critical frameworks to confront notions of history, truth, culture, and “justice.”1 Curatorial work holds opportunities for envisioning and representing stories, vernaculars, and symbolic interpretations. The practice (de)constructs meaning for diverse audiences; it offers a method of multisensorial engagement that challenges our assumptions of what we consider typical or traditional. It also brings the curator into relationship with the visitors and holds them accountable to the artwork or information on display and the ways in which their ideas shape the overall visitor experience.

Given the current political and environmental crises, we must respond with the tools we have at hand. I implement a grassroots approach to curation, building from the ground up, using whatever available resources to bring an idea to life. I draw inspiration from the local community, its residents, and the sociopolitical context of the ecology. The city’s landscape bears centuries-old histories that remain with us through the present-day interaction with its land and waters. My visits to India Point Park are coupled with reflections on its former role as Providence’s first port and its maritime activity that consisted of cargo shipping, including the notorious transport of enslaved Africans and Cape Verdean migrant workers. Elders have shared with me their memories of bygone family homes and restaurants, later demolished and replaced by private apartment complexes and luxury businesses. I incorporate these personal and community narratives in my work; stories that account for the overlapping nature of culture, economics, and environment and accentuate the truth in the popular feminist slogan, the personal is political.2 My experience with Providence’s forms of political activism and advocacy have exposed me to new methods of creative experimentation and alternative vessels for communication. Local grassroots organizing embodies the accessibility and transparency crucial to any work that aims to contribute to social transformation.

Still from the poem/video, "Our Bodies Back" Jonzi D and jessica Care moore, in "Black Sonic: Heritage as Heresy" exhibition curated by Melaine Ferdinand-King, FADA Gallery, University of Johannesburg, South Africa. Courtesy of Melaine Ferdinand-King.

In applying aspects of my grandmother’s teachings and organizing strategies to my curatorial endeavors, the exhibitions I’m involved in must be a collective effort fueled by artists and creatives with a shared mission. The exhibition should be a catalytic experience that interrogates how we define and conceive space, creation, belonging and reality itself, while presenting avenues for further exploration and productive discussion. As an emerging curator, my work moving forward is to forge gathering spaces that allow people to engage with difference harmoniously, to bring new meaning to the conceptualization of “art,” and, perhaps most importantly, to highlight the rich and underrepresented creativity that has always existed in the city of Providence.

Merriam-Webster defines “praxis” as the practical application of a theory.

The slogan “the personal is political” was popularized by Carol Hanisch in her now iconic Women’s Liberation Movement text from 1969.