From the PCG Archives – Student Perspective: The Aztec Sun Stone in “On the Wall: Tamara Gonzales”

Text by

Sara Conway

Written May 5, 2021

In March, On the Wall: Tamara Gonzales opened at PCG’s Reilly Gallery in the Smith Center for the Arts. Central to this large-scale piece that the artist has subtitled “Cosmic Recess” and made to dominate the walls is a playful ball game. Each of the three or four balls bouncing around are renderings of the Aztec sun stone. Viewers become immersed in this game, surrounded by the liveliness of “another world.”

Sometimes a ball appears beneath floating legs; other times it is momentarily trapped between a figure’s feet, like a soccer ball about to be kicked. The game may start again at any moment. The sun stone bounces between the humanoid forms, sometimes rests underneath a foot, a quick trap as another figure lifts a leg to go after the ball, the tension of the game rising.

The sun stone is repeated across the four walls of the space, and Gonzales considers them to be “both balls or planets,” forming a connection with the subtitle “Cosmic Recess.” Each sun stone is a different color, blue and black or red and orange sweeping across their surfaces, adding to the vibrancy of the game.

There are many names for this carved disk, including calendar stone, but “sun stone” is more accurate. The engravings on its surface “records the origins of the Aztec cosmos” and the cycle of time. (source) The Aztec sun stone documents the eras that have passed (suns) as well as the current one. In this system, our present day is the fifth sun but is called “Four Movement.”

The four squares in the center indicate the different eras, and each period has a specific image assigned to it. From the top right moving clockwise is 4-Jaguar, 4-Wind, 4-Tlaloc/Rain, and 4-Water. This naming system is based on what will cause the destruction of that era. Thus, it is “death by [the era’s name].” Four Movement—the present world—was prophesied to end by earthquake. The Aztec capital, in fact, fell near volcanoes and fault lines.

Originally, the Aztec sun stone was brightly painted. Scholars believe that the stone was created during the reign of Moctezuma II (1502–1520) because his royal insignia is present above the central figure. Furthermore, unlike its positioning in the National Anthropology Museum in Mexico City, where it hangs vertically on the wall, the disk was supposed to be facing up on the ground. The sculpture remains unfinished, noted by the thick pieces of stone still attached.

Nahua mythology notes cycles of creation and destruction, which are symbolized through the sun stone and its four suns. In order to keep the sun alive and encourage time to continue, the Aztes would sacrifice a prisoner on the stone itself on the day they believed the world would end. This ritual of human blood was believed to “feed” the sun and preserve the world. (source)

The face in the center of the sun wears ear spools—an indication of elite status—with its mouth open and tongue out. There are various interpretations of who is depicted. A possibility is the sun god Tonatiuh. Another recent argument is made by an art history professor at University of Texas at Austin, David Stuart. According to Stuart, this face could a “named portrait of the ruler Moctezuma II as a ‘sun king.’” The name glyph above the face could be a label rather than solely an acknowledgement of when the sun stone was created. As Stuart states, “In Méxica art, name glyphs seldom function as standalone entities and are instead almost always found in conjunction with portraits and images as a means of image identification.”(source)

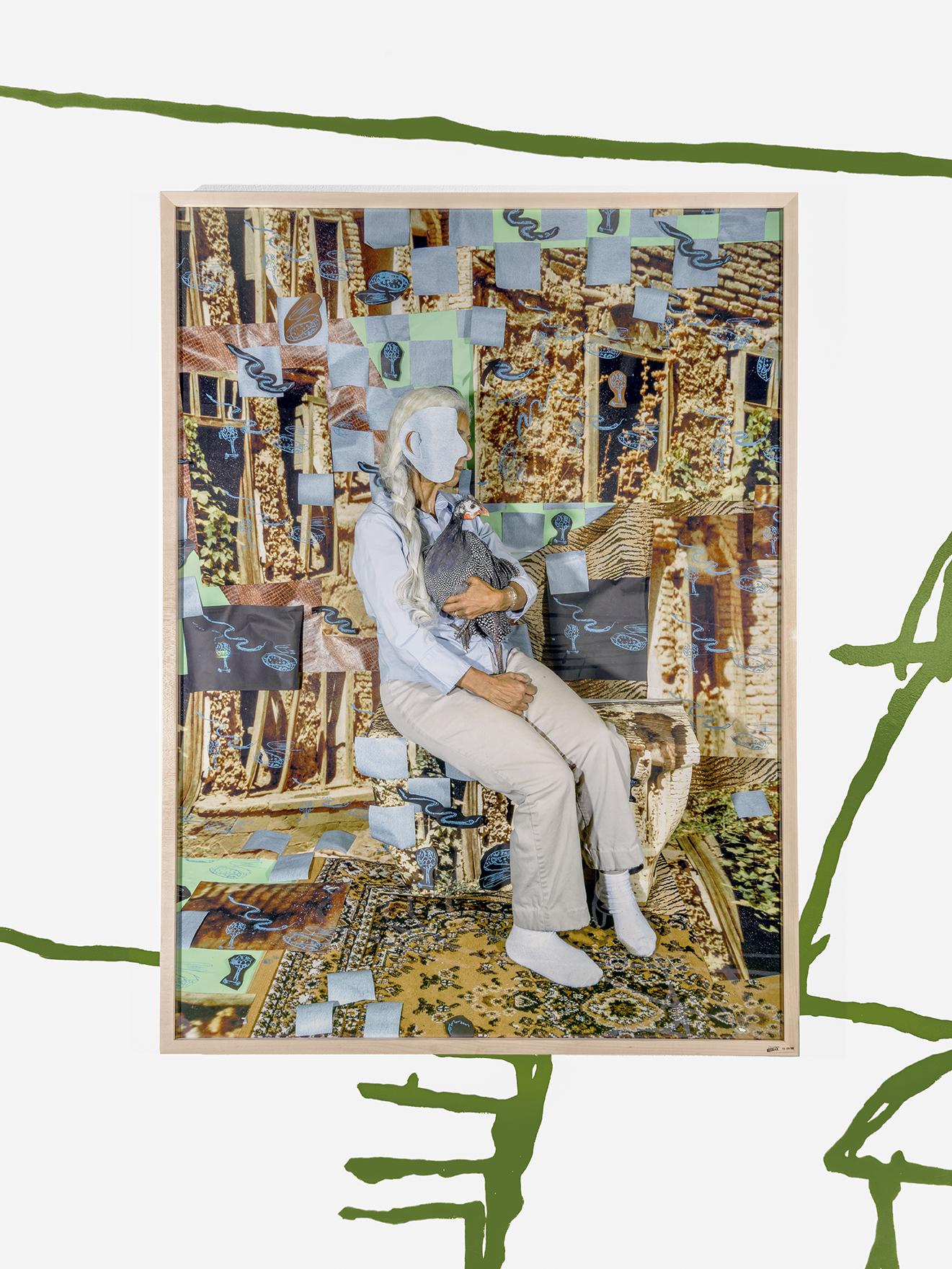

Tamara Gonzales, “Twice Born (Dionysian)”, 2014. Acrylic and spraypaint on canvas. 65 x 57 inches

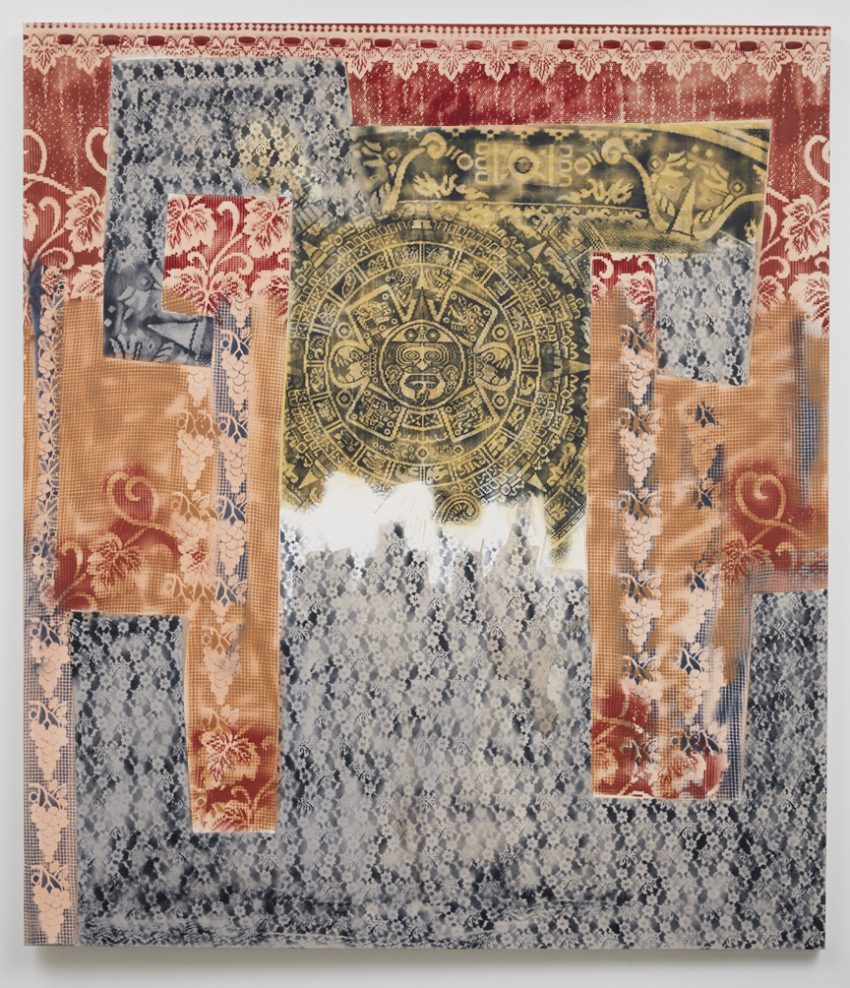

Cosmic Recess is not the only time Gonzales incorporated the Aztec sun stone into her art. The stone appears in her piece Two Moons from 2014, where it is a ball in a game, similar to Cosmic Recess. Gonzales’ piece Untitled from 2016 was woven in Cusco and “translated into an alpaca tapestry.” Even in its simplified form, the sun stone is still clearly recognizable.

Tamara Gonzales, “Untitled”, 2016. Alpaca and wool. 36.5 x 23.5 inches

Just as the Aztec sun stone has survived centuries of climate changes, open air, and mistreatment, so too has its imagery and history, which carries on through the work of contemporary artists like Gonzales.