From the PCG Archives – Student Perspective: Gender, Power and Craft in Kirstin Lamb’s Painted ‘Embroideries’

Text by

Jessica Rogers

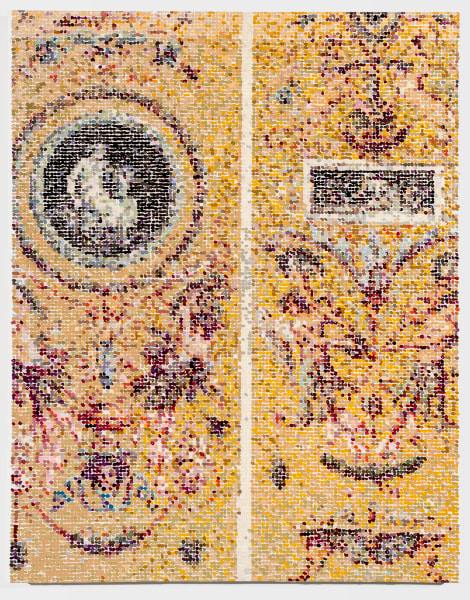

Kristen Lamb (b. 1979), After French Decoration Version 4, 2018.

Written November 11, 2018

As a dual psychology and studio art major, psychological concepts and theories I confront in my classes often mysteriously work their way into my everyday life, and can be applied to many encounters I have with both people and works of art. Providence-based artist Kirstin Lamb creates beautifully-intricate pieces that she refers to as “embroidery paintings,” and a group of them from PCG’s art collection are on view in Classic Beauty: 21st Century Artists on Ancient [Greek] Form, exhibited at PCG.

Lamb participated at a mini-symposium event held on the occasion of the exhibition’s opening, during which she talked about the breadth of her practice and the various themes that influence and live on in her work. One recurring theme Lamb discussed—and that resonates with me most—dealt with women and gender roles. Specifically, Lamb spoke about how the craft of embroidery historically was a predominantly female duty, or a category of “women’s work,” which mandated that women only be allowed to certain cultural expectations and limited process shows admiration for the craft as well as inquiry toward the gendered tradition. For me, Lamb’s work within the Classic Beauty series seems to address principles and concepts within the discipline of gender in psychology.

In psychology, Eagly’s social role theory of gender 1 asserts that physical differences between men and women are a causative factor in the development of gender roles. This theory suggests that individuals and society as a whole inadvertently pick up on physical differences between men and women, and base their behaviors and actions on associations with these physical variances. Similarly, gender culture is defined as society’s understanding of what is possible, proper, and perverse in gender- linked behavior. More generally speaking, although there are far more similarities than differences between gender in terms of cognitive abilities, like intelligence, capacity to learn, and problem-solve, fixed gender-role stereotypes can perpetuate the idea that men and women have different capabilities that require them to take on distinct roles in society. Thus, for arts and crafts like embroidery that historically have been considered “women’s work,” it becomes understandable that women have been pushed by society to be the central producers when applying ideas pertaining to the social role theory and gender culture. Although and women are naturally very different, gender-role stereotypes likely have contributed to the clearly-defined roles and guidelines set for women in history.

Lamb’s artworks seem to address these concepts and question the gender-role stereotype. These ’embroidery paintings’ mimic the intricacy and physically labor-intensive nature of embroidery through the act of painting, which was, until the last century or so, categorized by the academy—first in Ancient Greece—as a fine art discipline only suitable for men to study and professionally practice. With these artworks, which Lamb designs using embroidery methods and then paints using the tools and color theory principles she learned as a student at an art academy, she collapses historically defined gender roles. Furthermore, this particular group of embroidery paintings feature imagery drawn from wallpaper designs of the French Neo- Classical period, an era when the furnishing of aristocratic homes became an exercise in displaying power and stature. By adopting these motifs and laying claim to them through her laborious painting techniques, Lamb concerns: the gendered history of painting, restrictions on what content has been socially-acceptable for use by women, and more broadly, contemporary culture’s shifting ideas on gender roles that endure as legacies of pervasive practices, policies and philoshopies.