From the PCG Archives – Student Perspective: A Personal Reflection on Caitlin Cherry’s Dirtypower

Text by

Nina Askew

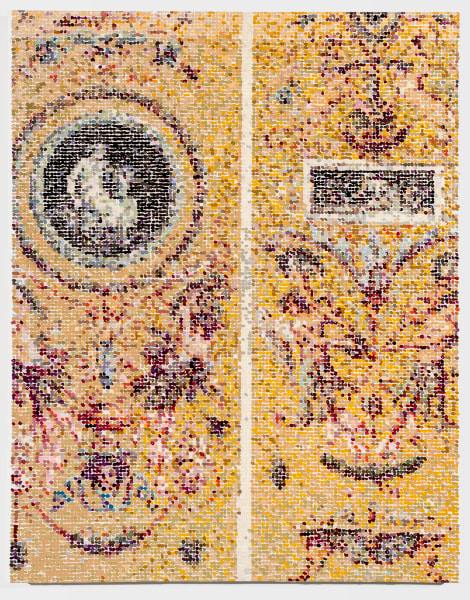

Caitlin Cherry, Installation view of “Dirtypower” at PCG. Image Credit: Scott Alario.

Written February 2, 2019

In approaching Dirtypower, Caitlin Cherry’s solo exhibition at PCG, I truly did not know what to expect. My lack of experience with contemporary art left me feeling pretty nervous. Would I be left looking at a group of paintings and sculptures desperately trying to decipher the deeper meaning of each piece?

The exhibition and artist talk was ultimately like nothing I had expected. I loved how Cherry explained her intended meaning of the work and the broader themes that she explores. Her approach felt so present and relevant to our current day and age. However, this relevancy was not made immediately apparent to me by just glancing at the work. Before going into her talk and panel, I peeked into the exhibition, and was frankly a little confused at the different color schemes and the skewed placement of the canvases.

During her talk however, I learned that the technique of coloring in her work is called solarization. The solarization of her paintings stood as a metaphor for the everyday problem experienced by technology users. The coloring of her paintings is aimed at mimicking the distorted coloring of our laptop screens when they are tilted a little too far away from our field of vision. What was once a clear, easy to see screen becomes distorted and strained. This manipulation of perspective is woven through the installation both in terms of color palette and the angular placement of her canvases.

While pushing the boundaries within the norms of color and pattern, Cherry also calls into question the accepted notions of the basic canvas itself. I have never once thought to myself: “Why are all canvases the same shape? Why are they all square?” Her description of a canvas as a window presented an answer to a question that I have never event thought to ask. By tilting her canvases and positioning two of them together, it prompts the observer to take a new perspective on her piece and a new awareness of their own body as a viewer.

Caitlin Cherry, Installation view of “Dirtypower” at PCG. Image Credit: Scott Alario.

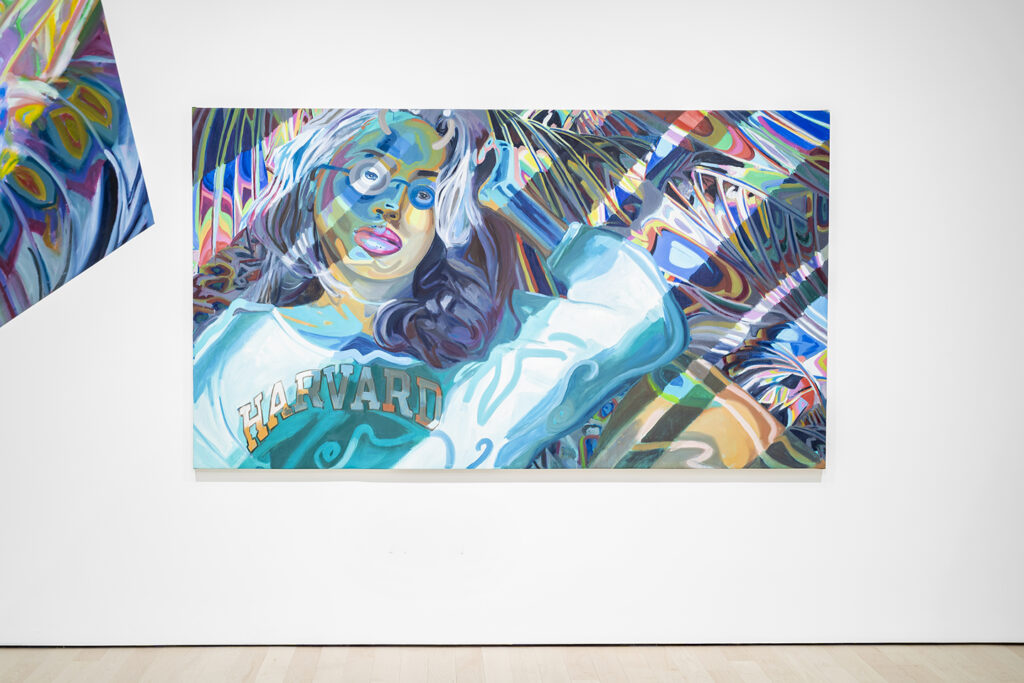

My favorite piece from her presentation was not included in the show, but was titled Sea Dragon Leviathan (2018), a large painting depicting a women sitting on the inflatable whale next to a swimming pool. At first glance, I was a little confused at the figurative combination of woman and lizard. By replacing the woman’s head with a lizard’s took away from the appeal of the painting, and I initially was at a loss for the reasoning behind why she did that. Per the artist, there are two themes present in this particular work – sexuality and caricature.

By removing the woman’s face it forces the viewer to acknowledge the woman’s body first. The removal of her face has taken away the most personal and identifiable feature of this woman’s form, thus stripping away her identity as a human being and transforming her into a primarily sexual being. Does emphasizing the sexual charge of the original photo take ownership of the narrative? The way I interpret this artwork is that this woman is taking control of her body. From a young age, women are told how to act, and what to wear in an effort to protect our purity and preserve our reputation. However, this woman is breaking all the rules imposed by society to suppress women’s expression of our sexuality. By wearing a bikini and posing butt first she is forcing society to accept her as a sexual being. She is ignoring the restrictive rules that repress women.

Sea Dragon Leviathan, 2018. Oil on canvas. Image courtesy of the artist.

In the same way that the woman is rejecting preexisting rules in society, so is the artist. Facial features offer the most direct and primary was of displaying beauty through portraiture. However, the artist is rejecting that rule and displaying beauty through the model’s body. The beauty of the woman cannot be found through her face, so one must look for it in her physical form.

Throughout history, black people have been displayed in media with a variety of different derogatory stereotypes. Big lips, “uneducated” slang, monkeys, are a few of the characteristics that society has chosen to emphasize in order to dehumanize black people. As an effort to reclaim these stereotypes, Cherry chooses to depict this woman facially as a lizard. In the way the public has tried to dehumanize black people by displaying them as these caricatures, Cherry is reclaiming the negative connotation through such a considered act. By not giving the public the power to take away our humanity these characteristics that were once embarrassing are now seen as beautiful. Art displays beauty, and since this artwork over-exaggerates the model’s big lips and eyes, those characteristics are now something to be proud of.

With the contemporary rise of a new era of feminism, women are reclaiming their bodies. Instead of obedience and deference to society’s calls to cover our bodies, or be modest, the newer generation of women are liberating themselves of society’s rules that have been restricting us for centuries. Instead of hiding or being shameful of our bodies, we are embracing their natural beauty. The freedom, acceptance, and pride women feel towards their bodies is causing us to take ownership of their public display.

Caitlin Cherry, Installation view of “Dirtypower” at PCG. Image Credit: Scott Alario.

Running parallel to women reclaiming the beauty of their bodies are black Americans reclaiming their rich culture. The widespread movement of black pride, that has been in existence for decades, is an example of black people reclaiming the stereotypes that have been hurled at us since we were forcefully taken into this country. We are reclaiming our culture, one aspect at a time, and appreciate its beauty. No longer will we be told that we are not beautiful, or worthy. We are taking our power back and reclaiming our humanity.

Another facet of Cherry’s work that I particularly loved was how she exclusively painted black women. The perspective of the black woman is one that often gets left out, and overlooked in society. The inclusion of black women in her exhibit is the first step in letting our voices be heard. Today an art exhibition, tomorrow, the world.

Chaos Compressorhead Leviathan, 2018. Courtesy of the artist

The banding of the color schemes in the portrait of Lil’ Kim was something that I did not even notice until she pointed it out; a reference to visual glitches typical of old-fashioned televisions. The existence of this visual banding also plays into the reoccurring theme of perspective. From up close the banding is not noticeable, however as soon as one takes a few steps back they become more obvious and even distracting.

Cherry refers to these women she paints as her muses, which bestows on them a title I believe is deeply rooted in a sense of humanity. Society often views Instagram models as these less-than-human women who do everything for attention. By labeling them as muses, and asking them for permission to paint their photos, gives them both agency and identity. It acknowledges their bodies as art, and displays Cherry’s understanding that even though their art takes the form of an Instagram post, it is still a form of art, one that must be properly credited. The term “Instagram model” has a negative connotation, while the term “muse” has this majestic, dignified, desirable, positive connotation behind it. By relabeling these women it is re-humanizing them and in turn dignifying their art and their point of view.