Impossible Flying and Eco Pedagogy

Text and Images by

Dr. Maia Bailey and Eli Nixon

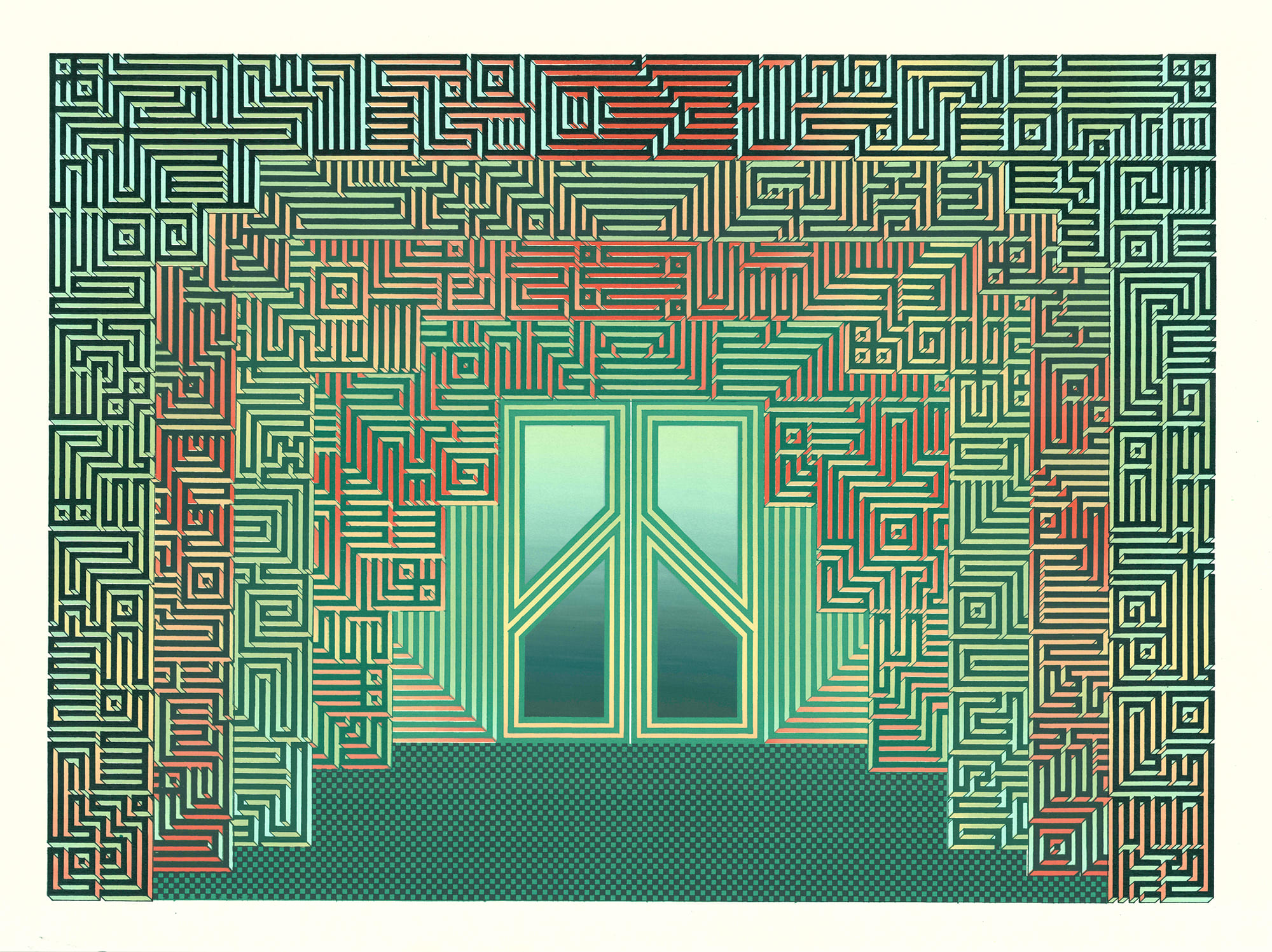

Eli Nixon, "Impossible Flying," Bloodtide, 2021

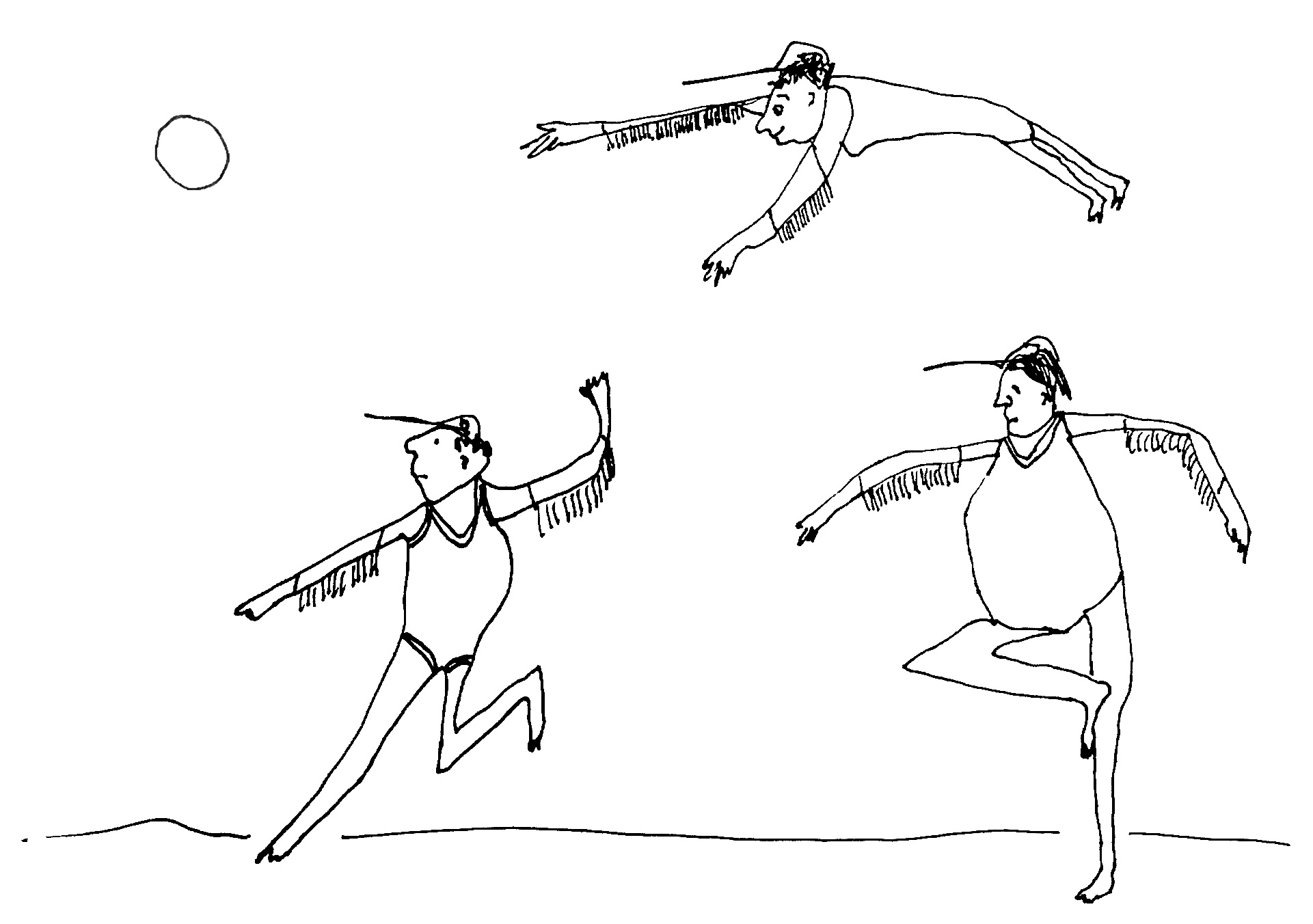

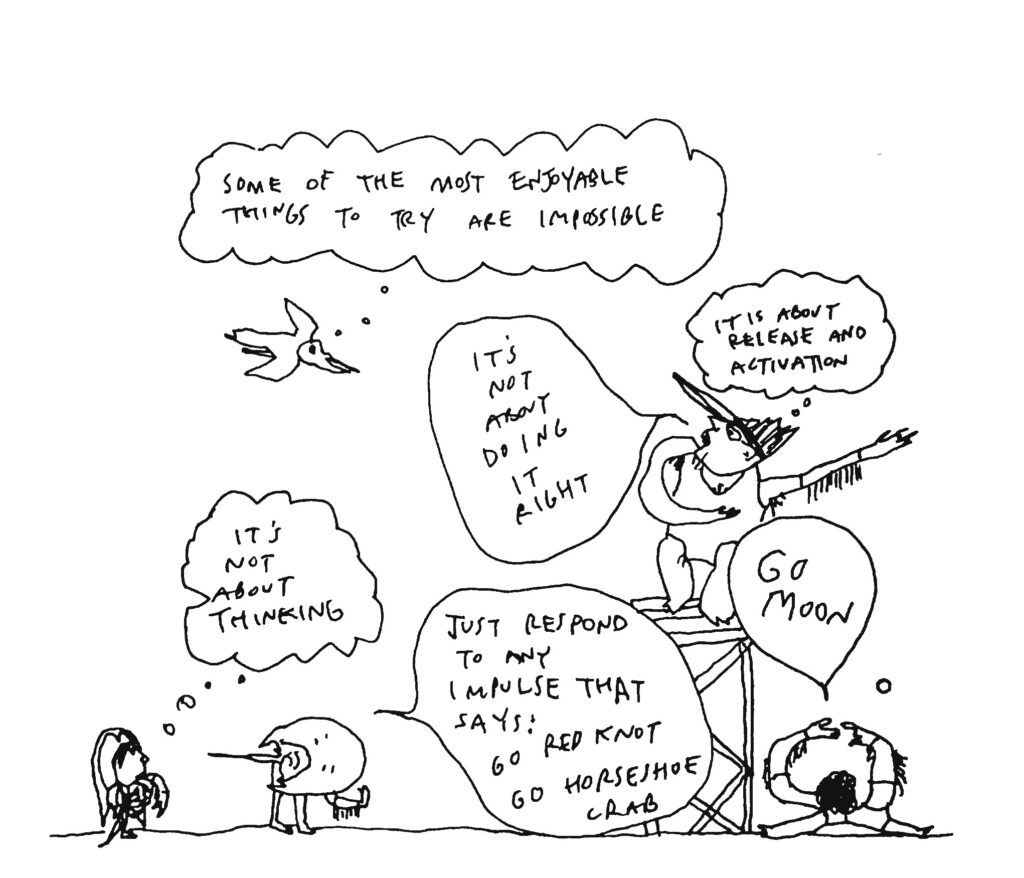

I’ve just had a great conversation with Eli Nixon. They are a visual artist, puppeteer, activist, and the author of Bloodtide, a book that proposes a new holiday in homage to Horseshoe Crabs.1 My favorite part of the book is the Manual section suggesting different holiday activities designed to both celebrate and teach, like making Detritivore Pie, doing a Tick Check, or performing nature-drag–inhabiting a horseshoe crab or red knot (creatures part of Rhode Island’s ecosystem) as a way to imagine new possibilities for ways of being in relationship to oneself, each other and the “natural world” (of which we are also a part.).

Me? I’m a Professor of Biology. My background is in the evolution of plant mating systems, meaning the ways plants divide up the tasks of making pollen and seeds. At Providence College, I teach courses about evolution, ecology, botany, food systems, and gender. You can guess that Eli and I have in common a love of the outdoors, but we also have in common an emphasis on teaching through doing.

Eli Nixon, "Relax," Bloodtide, 2021

When I was just starting out as a college professor, I thought my job was mainly to explain content. But explaining only goes so far. If I really want students to remember and incorporate new ideas into their model of how the world work, they need to learn by direct experience. To create situations for direct experience, a teacher sets a scene like a director of interactive theater. For example, performing experiments helps make science concepts concrete and build deep connections through observing processes in the real world. For example, when I teach about plant nutrition, we go out and measure soil nutrients on campus.

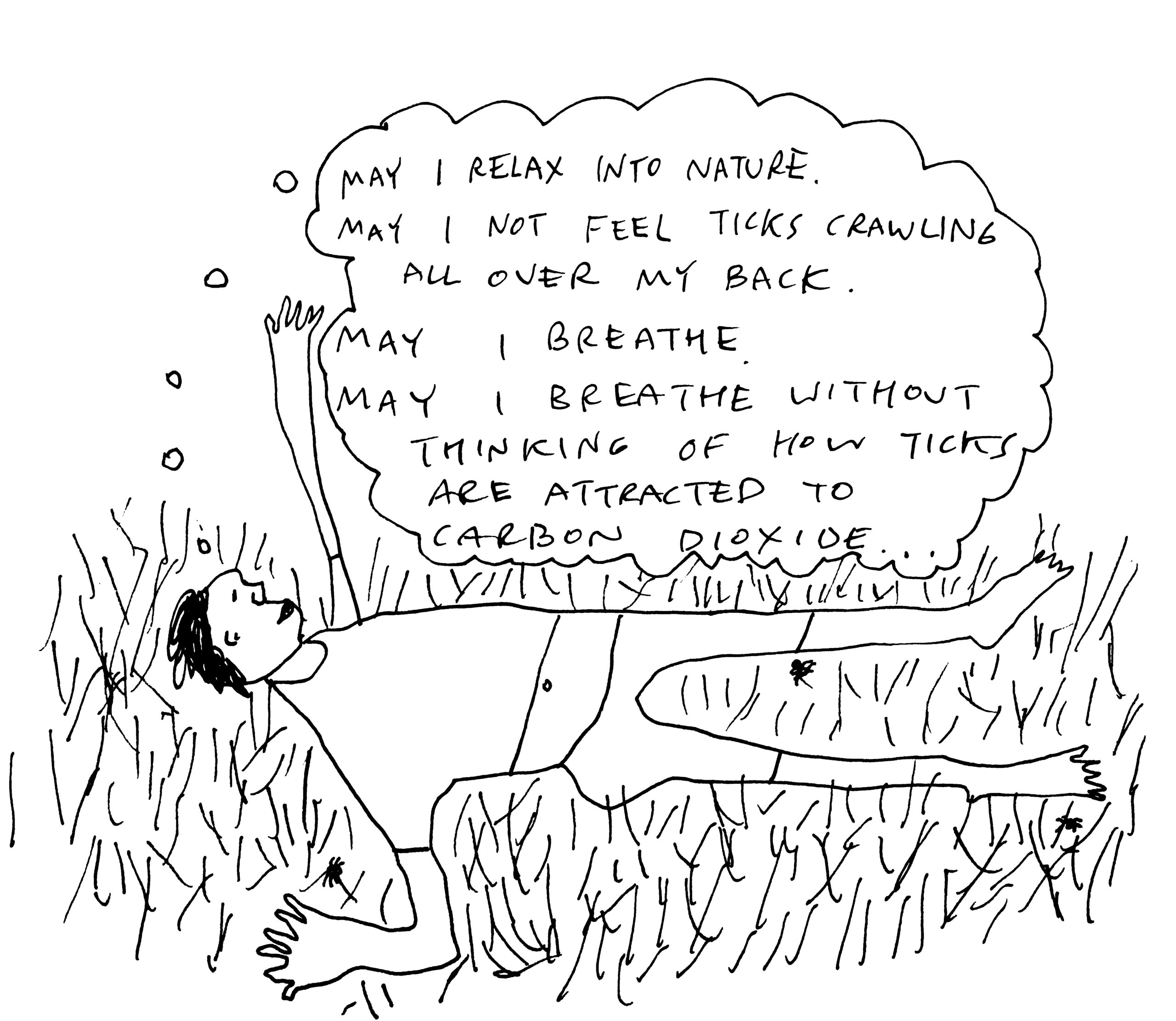

Eli Nixon, "Maybe You Don't Speak Moon," Bloodtide, 2021

I have also learned that I need to teach attitudes and values as well as concepts. Climate change directly threatens the natural processes that my students and I study. I want my students to be able to enjoy a thriving natural world throughout their lives, and I need them to help change how we treat nature individually and collectively. But how can I as a science professor incorporate values and ethics into my courses? One approach I have used is incorporating texts like Pope Francis’ Laudato Si’ and Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass that discuss ethical treatment of nature from different religious traditions. These texts tell us why we should value nature beyond its direct effects on us. In different ways and traditions, Catholicism and Indigenous American religious practices teach that to be good as humans is to see nature as deserving respect and love. But to cultivate love, we must know and interact with the beloved. We must grow empathy for creatures other than ourselves. In other words, we need to understand the world from their point of view.

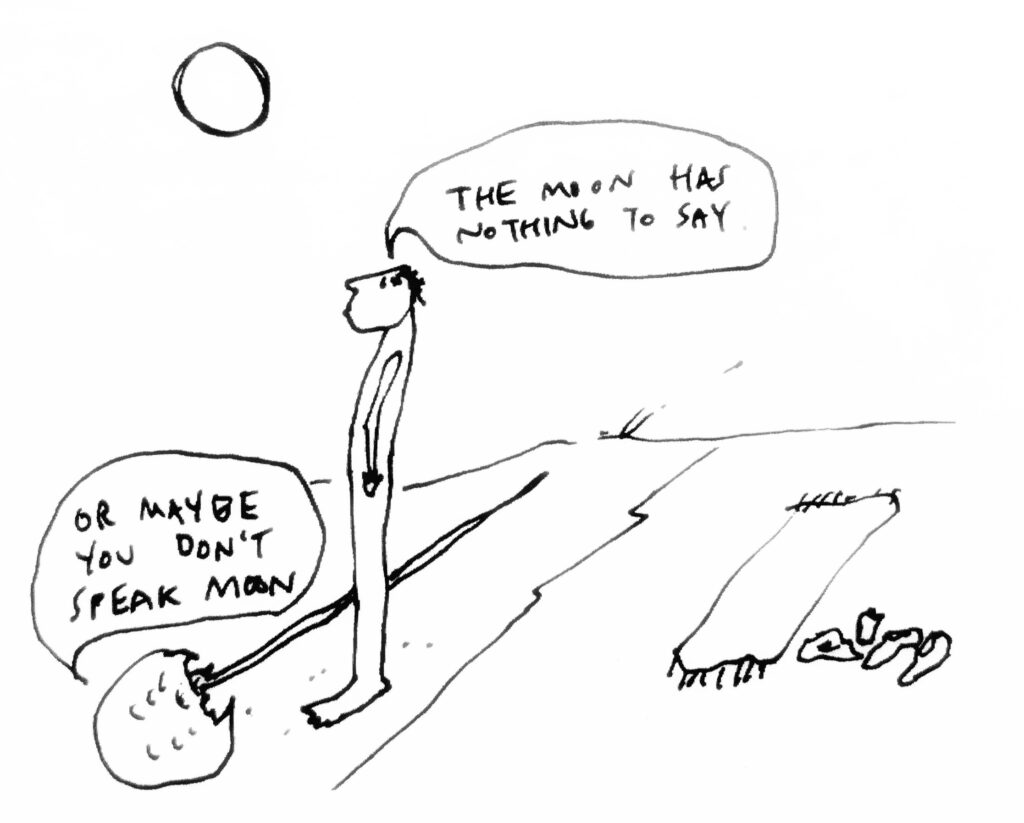

Eli Nixon, "Keep Trying," Bloodtide, 2021

What I love about Bloodtide is it helps us celebrate and value a neglected organism often seen as alien and unknowable through activities that center non-humans, encourage growing empathy and imagination, endeavors the “impossible,” and is never preachy or boring. Eli is an eminently skilled playwright, creating scenes for us to explore, where we are the actor and audience, and in the end are transformed by play to see the world anew where the moon has a powerful pull, we eat with our knees, and horseshoe crabs dance with red knots.

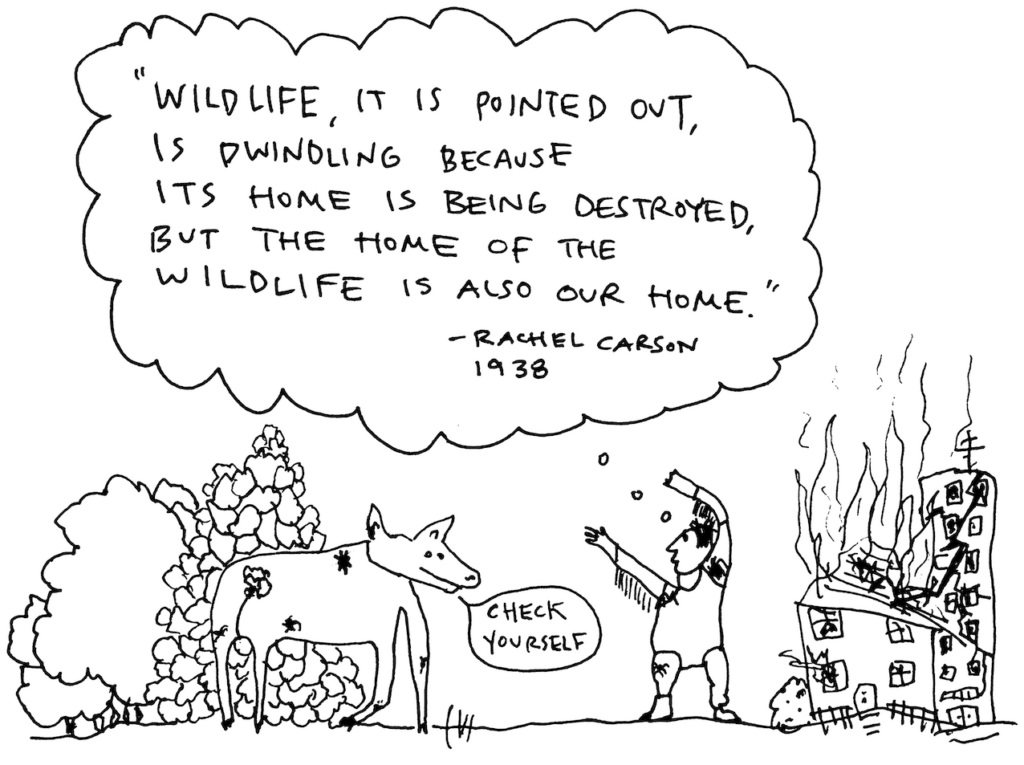

Eli Nixon, "Wildlife Dwindling," Bloodtide, 2021

I teach about plants not horseshoe crabs, but reading Bloodtide has sparked my imagination for how I can be a better playwright for my students. Next time I teach, I might ask students to try to eat like a plant or choreograph the dance of flowers and pollinators. And I will try to remember for myself and my students that “It’s not about doing it right. It’s about release and activation.” It’s about recognizing and grappling with our ongoing enmeshment with the more-than-human world, in all its gloom and glory.

Eli Nixon, "It's Not About Doing It Right," Bloodtide, 2021

All images courtesy of Eli Nixon, Bloodtide, The Third Thing Press, 2021.