WEATHER FORMS (RI BAND): Leah Beeferman

Liz Maynard

on Leah Beeferman

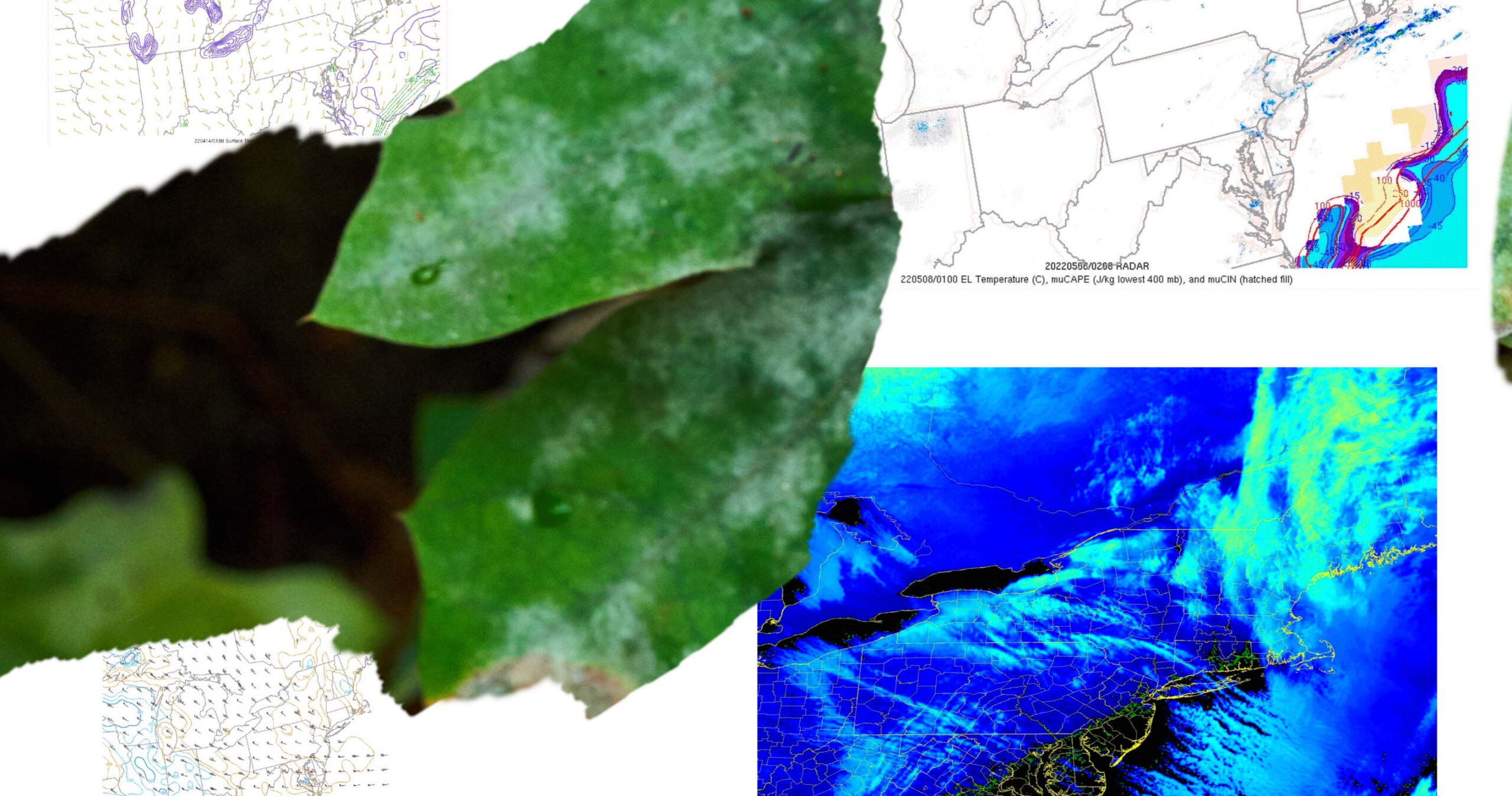

Leah Beeferman, WEATHER FORMS (RI-BAND), detail, 2023

Editor’s Note: The above image is a detail; see the full artwork here.

Maps are often meant to orient us: to tell us where we are or where we’re going. Leah Beeferman’s digital installation WEATHER FORMS (RI-BAND), (2022) at once tells us both too much and not enough. Scrolling through her expansive ecosystem-made-visible, composed of enlarged views of local foliage to maps of wind movement to atmospheric pressure shifts and everything in between, I get the sense of being situated in a landscape that is both familiar and unfamiliar. Although I cannot really allege to understand Beeferman’s quoted maps, they evoke a language I think I know, perhaps from a youth spent watching the weather channel on television, or more recently, my chosen phone app.

Wind embodies this liminal quality. It’s both absolutely palpable yet invisible. The wind is seen in the bowing trees and blowing leaves: we see its effect rather than the force itself. As an art historian, I think of the long tradition of rendering the invisible in tangible form. I recall cartographic illustrations that show forceful winds with puffed up cheeks and angry brows, or Botticelli’s anthropomorphized Classical zephyrs swooping in from the margins, by turns benevolent or malicious.1 Jessie Wilcox Smith’s ethereal children’s illustrations for George MacDonald’s moralizing adventures At the Back of the North Wind. Or even the near-absurdist maps of the Situationist International’s “psychogeographies,” which track the unpredictable, drifting movements of SI artists as proposed energetic, rather than literal, maps of sites.2 Artists have long tried to visualize what shapes and animates us, what literally moves us.

Leah Beeferman is especially interested in this process of translation, always an evocative rather than a literal process. Many of her works are about translating her own deeply subjective experience of her surroundings. For instance, RAIN FOREST (2019) was recorded at the Tiputini biodiversity Research Station in the Amazon rainforest in Eastern Ecuador. Visual fragments of lush forest are layered with her voiceovers, visuals and narration each attempting to convey the experience while only able to offer a piece of the whole. Beeferman “explores the density of the rainforest by considering what is not seen: either because it is hiding or hidden, or simply because there is too much to see.” As she tries to re-present her experience of these densely rich spaces, she continually bumps up against the awesome truth of its impossibility.

WEATHER FORMS has roots in Beeferman’s interest in scientific tracking and gathering data, practical attempts to orient in the oft-invisible atmosphere, though its shifting is palpable everywhere around us. The work arose out of her use of particular phone apps that collated weather data, her growing dedication to them linked to increasingly dangerous climate change denial. Even in the face of all this change, it’s sometimes hard to conceptualize the link between something as ethereal as wind to the foliage we’re surrounded by. Perhaps especially in an urban setting like Providence, where the visual cues of leaves in the wind are a bit less common. Such data maps are meant to help us navigate the chaos of natural disasters unfolding globally, of why our seasons feel different than a decade ago, but their supposed cool clarity and scientific objectivity is further muddled when we confront the question of what happens when we simply don’t trust each other’s world views?3

Beeferman’s work invites us to wander(scroll) through a digital landscape, but refuses to orient us. It scales in and out, from the minute foliage at our feet to the shifting pressure systems above and all around us. We’re caught in between the micro and macro, not just interpreters of opaque data, but embedded within the imagery’s calculables: topographical, thermal, mathematical, botanical. In this oversaturation of imagery, I am even more aware of the kinds of information filtering we’re constantly performing to not feeling overwhelmed by the sheer amounts of data we’re surrounded by. What does it mean for me to really know the data in the map the I’m looking at, if it’s in a language I was never trained to interpret? Can I really recognize this microfauna, zoomed up to monumental scale? Probably as something I’ve inadvertently stepped on moving about my day.

Beeferman’s intent is not to completely overwhelm us, but make the synaptic connections between the abstract and the felt-sense of our atmosphere. Weather, she says, is a universal. It’s something that we all have an experience of; so common to that social adhesive, small talk. Maybe in her juxtapositions we can get a sense of our own scale. Just as the awesome-ness of the rainforest is hinted at but never truly translated in Beeferman’s work, perhaps the disorientation of WEATHER FORMS helps remind us, and hopefully motivate us, to grasp the incredibly complex matrix of the atmosphere, of which we are a small, yet crucial, yet destructive, and hopefully reparative piece.

Zephyrus’ rape of Chloris is sometimes interpreted as a corruption of innocence in the Renaissance Neoplatonist reading of Botticelli’s painting, but the recent action of climate activists at the Uffizi in Florence, Italy, in which two protestors glued themselves to the glass cover of the painting (with special care to choose glue that would damage neither the glass nor the painting), evokes the idea of nature as vengeance. As the site of a climate protest, the rape of Chloris by Zephyrus becomes a critique of the exploitation of the land.

Guy Debord published his Theory of the Dérive in the second Situationist International (1958). He describes the dérive as “a technique of transient passage through varied ambiences.”

Beeferman engages Karen Barad’s theory of agential realism explored in her book Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter in Meaning, which accounts for the world as a whole, rather than divided into separate realms, like the “natural” and the “social.”