TÁR and Romanticism’s Sharp Edges

Figure 5. Still from Tár (dir. Todd Field, 2022) demonstrating Apodaca’s sense of the camera breaching Tár’s privacy.

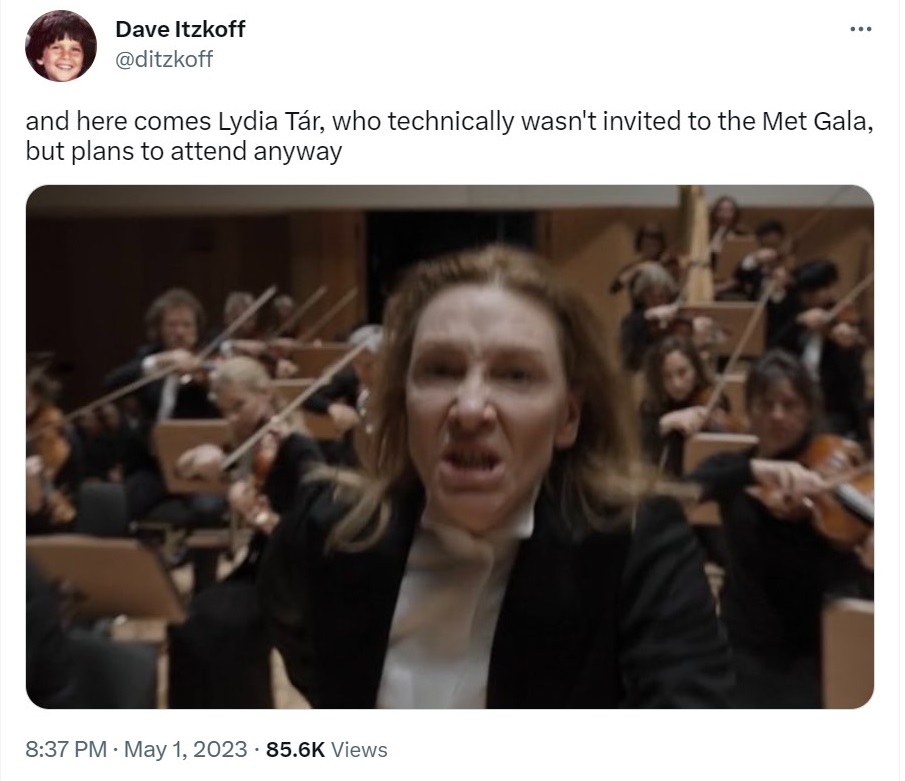

Judging by the articles and memes generated by prominent publications including the New Yorker and cultural critics like Dave Itzkoff, the film Tár (dir. Todd Field, 2022) is a hit with a certain kind of movie lover (fig. 1). It’s an emotionally intense exploration of artistic and personal obsessions centered around Lydia Tár, the titular orchestra conductor, at turns funny and horrific. Substitute a period-appropriate reference and the previous sentence could describe the broad artistic movement—perhaps better understood as a sensibility—called Romanticism.

Figure 1. Dave Itzkoff (@ditzkoff), “and here comes Lydia Tár, who technically wasn’t invited to the Met Gala, but plans to attend anyway,” text and screenshot of Tár, tweeted May 1, 2023.

This past semester, I worked with four Providence College students to define historical, Euro-American Romanticism, which dominated salons in the early- to mid-nineteenth century. We also explored non-canonical, global, and contemporary art that might be called romantic left out of standard textbooks. Our framing essay was a famous 1846 tract by the poet and critic Charles Baudelaire.1 To Baudelaire, Romanticism was not really a period style, but rather an indefinite and popular “way of feeling.” Since the mid-nineteenth century, historians have agreed that the sensibility focuses on searching, emotional self-expression, but some later scholars such as Robert Rosenblum have identified it as an ongoing tradition.2

I watched Tár with Zari Apodaca (PC ’23, Art and Art History), James Geraghty (PC ’23, Art History), Anthony Tinaro (PC ’25, Art and English), and Quan Tran (PC ’23, Art and Art History) to cap the spring semester.3 They responded to the film based on our semester-long study. I also asked them to submit one of the many memes circulating online about Tár that they thought best fit the movie’s romanticism, some of which illustrate this essay. Together, we’ve identified how writer-director Todd Field and his star, Cate Blanchett, participate in and complicate Romantic discourses.

Time and Timelessness: Tár’s Chronomancy and Romanticism’s Sublime Eternity

Romantic artists made the tension between humanity’s mortality and divine or endless time a fundamental artistic concern. We read and discussed Thomas McFarland’s examination of fragments in seminar. In his book, McFarland argues that Romantic poets turn fragmentary ruins into imaginative portals to eternity.4 They achieve this by collecting and framing historical objects and texts within their own projects. Artists dissatisfied by the limitations of the historical record also created faux ruins: follies, pretend ancient sculptural fantasies, and architecture retrogressive in its antique style. Scholars reevaluating nineteenth-century archaeology highlight their antecedents’ literal reworking of the past, as in the so-called Mask of Agamemnon that some argue overzealous archaeologists altered to look more like a masculine hero.5

Fragments evoke the insignificance of a single human lifetime in comparison to the vast expanse of history, and, ultimately, the cosmos.6 Romantic thinkers thus imagine the fragment in context, searching for the missing whole it suggests. They love the fragment not only for its own contours, but also for the imaginary complete object its edges suggest. These intellectual fantasies become art that masters time—and achieves a kind of immortality—by carefully entwining the artist’s present work with the achievements of the past. In Tár, multiple characters collect, own, and alter the musical past, but the central character’s crises and triumphs best demonstrate Romanticism’s time and timelessness.

Figure 2. Quan Tran, Tár, Chronomancer, 2023. Digital montage.

Tár is time’s master when she’s in her musical element (above, fig. 2). Sometimes Field and Blanchett together make her what Tran describes as a “chronomancer,” capable of suspending and otherwise manipulating time. The term is associated with a class of beings in fantasy games and the East Asian practice of choosing auspicious dates for significant events.7 Blanchett’s Tár takes musical action with mystical conviction and unforgiving, technical precision, just as astrologers practice spiritual divination dictated by strict rules.

Tár’s equation of herself to time strikes Geraghty as particularly romantic, especially the conductor’s megalomaniacal declaration, “You cannot start without me.” Geraghty explains in poetic rhythm that Tár “is the start of time and the pace of time and the pause of time and the end of time.” Similarly, he reads the character as self-obsessed and dismissive of the orchestra, believing that “the instruments, players, and sound are nothing without her” because she dictates their quality.

Tár’s magic is her ability to control the musicians’ time, which Tran notes, she “treats as an extension of herself, a profound part of her being.” Expanding on this idea, he argues that Blanchett’s embodiment of her character is in tension with her capacity to manipulate time. Tár’s gestures shape time with gentle caresses and sharp punches, but these movements are made of the fallible stuff of biological reality, what Tran identifies as her “very time-limited body.” For Tran, this constitutes one of Field’s most successful choices. He explains, “I like this conflict between her ability as an artist and her body’s capacity as a vessel to endure all the power that she appears to have.”

Framing and pacing communicate Tár’s centrality to the story, the relationship of time to her orchestration, and her emotional state. According to Apodaca, “When Tár is on screen, she is almost always the center of the frame which communicates the polarizing centrality she believes she has. This goes along with the belief that she herself is time, a central aspect of existence.” For Tran, the film’s “pacing sometimes mimics Tár’s orchestration.” To transition from non-musical, ordinary time to the mantic time on stage, “the slow and mellow dialogue grows into something much more intense and fast paced, much like the way she describes herself [and the music] when she’s conducting.” Geraghty finds that the narrative pacing reflects and reinforces Tár’s mental state. “At the beginning of the movie, I felt that the first few scenes were dragging…. Later, everything becomes much faster paced” as Tár’s personal improprieties are exposed. In so doing, Field communicates how “Tár feels when her life and her dreams slowly [and then quickly] slip away.”

Figure 3. Frontispiece to Edgar Allan Poe, translated by Charles Baudelaire, Histoires extraordinaires, traduites par Charles Baudelaire. Nouvelles histoires extraordinaires.... (Paris: A. Quantin, 1884). Source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France. Romanticism was a transnational project, as Baudelaire’s hit translations of stories by the American (and sometime Providence resident) Poe demonstrate.

Much of the film features not Tár the Chronomancer, but a person disoriented by her utter powerlessness over the linear progression of time. Field turns this unforgiving rhythm into a metronome, echoing sometime Providence resident Edgar Allen Poe’s incessant, Romantic, tell-tale heart (fig. 3). To Tinaro, the metronome “is a symbol of Tár’s rigid internal world which is only moved by music (to her family’s detriment).” Apodaca observes that Tár “deifies herself by finding everything surrounds her, especially in music.” In so doing, she sets herself up for disappointment. Time marches on with or without Lydia Tár. Apodaca explains, “In a radically progressive society, it is extremely difficult for the titular character to understand why anyone would forego music of the past. For that matter, she is deeply concerned with the past in general,” so much so “that she imitates an earlier conductor’s album cover for her own Gustav Mahler recording.”

As a scholarly community, we find that Field’s character Tár is deeply invested in Romantic fantasies of transcendent or sublime time. At the same time, Blanchett and Field demonstrate that Tár is lost outside of those fantasies. She’s so in love with her chronomantic power in the concert hall that she can’t seem to navigate the world outside. And as Apodaca points out, her power over time is connected to her art’s history and her obsession with Mahler’s Fifth Symphony.

Tár makes fun of a subordinate’s collection of musical knickknacks, portrait busts, and deadstock pencils, but she’s hardly clean of such sentimentality when her narcissistic drive for musical divinity blinds her. “Furthermore,” Apodaca observes, “her unhealthy desire to be perfect overwhelms her life, causing her to be rigid and void of feeling when dealing with others.” If you’ve seen the movie, then you know that this failure to empathize with family, colleagues, and subordinates is her undoing.

The Illusion of Genius and the Ghosts of Tár’s Past

Field and Blanchett unfurl their story through Tár’s search for a true interpretation of the musical past studded by terrifying apparitions of her personal failures. In nineteenth-century Romanticism, both the consequences of the past and specters of the future haunt the present, and according to Tinaro, a temporal rather than sculptural Ozymandias condemns Tár’s hubris in the film. “Time judges Tár in this film – death follows her around even when she expects to be most alone. Her attempts to shield herself from her own past with music come crashing down….”

Tár refuses to see that she is set within eternity even when she’s not on stage. As in so much of Romanticism, the lines between fantasy and reality, fiction and fact are blurred. Tár’s nostalgia is complicated by its false foundation, which is so often true of historical fantasy. She renamed herself, thus rejecting the class connotations of the name Linda, her family, her past, and the consequences of her actions. With these errors in self-conception, Tár is unable to consider her actions beyond the stage worthy of sustained attention.

Obsessive focus on work at the expense of every other part of life even unto death is central to the Western ideal of the genius and an important tenet of Romanticism. In this self-reinforcing narrative, artists committed to the emotional dimensions of aesthetic, spiritual, and political practices should match that work with an emotionally turbulent life. Baudelaire writes about this by arguing that the emotional creation of art must match is emotional reception. Since the mid-twentieth century, many scholars have questioned this idea because it valorizes suffering—and inflicting pain on others—as key to great art.

I brought the question of suffering and genius to the seminar often, especially in relation to the scenes Francisco de Goya painted in his home, which were long interpreted as symptomatic of the artist’s supposed madness.8 Last fall, I saw the so-called Black Paintings during a research trip to Madrid, and found them immensely powerful. Rather than signs of illness, I prefer to think of the artist’s late work as a period of self-exploration visualizing deep, real fears through unreal monsters. Goya transfigures the state, institutional, and interpersonal violence he witnessed into metaphysical criminals drawn from psychic depths — the witches, demons, and Olympian gods that populate his compositions. A fieldtrip to Madrid with seminar participants was out of my budget, but we looked at some of Goya’s original art, including prints and a painting, at the RISD Museum. A striking carbon black and watercolor painting in the collection exemplifies the artist’s expressive, psychological style (above left, fig. 4). Like the Spanish Romantic, Field turns to haunting to illustrate Tár’s inhuman commitment to genius.

Apodaca noticed that the ghosts of Tár’s past come through in Field’s camera work (above, fig. 5). She writes, “The camera angles are also interesting in the way that the viewer feels as though they are spying on the central character’s life. This breach of privacy parallels Tár’s attempt to hide the many secrets in her personal life,” secrets which soak into the story’s drama until they explode in the conflagration of Tár’s contradictions. Tár’s one-time protégé, an aspiring conductor named Krista, “has been the invisible antagonist this whole time,” Tran exclaimed. The contours of their relationship become clear only as the full extent of Tár’s damaging behavior shows up on screen.

Tár is a force to be reckoned with musically, and she is uninterested in reigning it in elsewhere. Cate Blanchett commands Field’s frame with fluid gestures punctuated by strange huffs and sharp tailoring, but she reverses poles with ease, turning her powerful magnetism into repulsion. Blanchett and Field transfigure Tár’s dream career into a nightmare, the inverse of her ecstasy in conducting (above, fig. 6). Per Tinaro, “The ‘ghost’ that haunts Tár’s career and personal life is Krista. Not only can she not escape the actual consequences of her potential crimes against Krista, but she also cannot stop herself from grooming young women and cheating on her wife. She is haunted by Krista, but the problem is herself, and no amount of success and fame is going to change that.”

(@LydiaTarReal), parody of a Notes app apology for Tár’s habitual inconsiderate behavior, tweeted January 15, 2023.

On screen, Tár belittles a student’s conducting, who in turn throws a gendered slur at the character, putting a fine point on Field’s revision of the masculine myth of the genius. Tár uses an institution built to further the careers of female conductors as an extension of her musical power and a hunting ground for sexual conquests. For a viewing public long comfortable with commanding, even violent creators rocked by increasing disapproval of sexual abuses of power, Blanchett’s embodiment of a similar violence is uncomfortable, and sometimes transgressive.

Nonetheless, both the film and my seminar collaborators are clear that Tár’s gift—her chronomantic power—does not repair the damages she causes (fig. 7). Even musically, she is stymied, to the point of never moving beyond a few, bare notes in her much-touted next opus. Perhaps her personal failings actually block her creativity, as in when she ignores her family and less pleasing work because she prefers to be, Tinaro writes, “in rapturous creation or with young, hot women. The movie makes an important point that whatever talent for music she has in no way excuses her for the way she treats people.”

Apodaca joins Tinaro in considering the film a deconstruction of the genius myth, writing that Tár “fits into all the stereotypical idiosyncrasies of the genius trope. However, as the movie progresses, we see that Tár is a fool because she has an over-inflated sense of self in her professional and personal life. Her disregard for others isolates her completely. Tár could possibly be a genius when it comes to the study of music singularly, however, her humanity or lack thereof is quite foolish because there is much more to actual success and fulfillment in life than professional accolades,” or so we hope.

So, Is Tár Romantic?

Despite rumors to the contrary and Blanchett’s striking animation of the character, Lydia (neé Linda) Tár is not real. However, her warning about the dangers of losing perspective in the service of art and power is. Apodaca identifies this clearly, “Throughout the movie, Tár asserts that the purpose of music is to get the audience to hear the conductor’s and players’ emotions through instruments…. She encourages her students and others to abandon physical expectations and rules and embrace the metaphysical aspects of music. For Tár, music is the only place that she can safely feel something without the guilt and morality of the outside world.” Romanticism is, among other things, the artistic tradition of searching for the relationship between the individual and everything else. Singular focus on the self, as Apodaca explains, through the metaphysics of art—whether music or any other form—can lead to willful ignorance of others.

Both Geraghty and Tran identify the film’s emphasis on the central character’s emotions and her fantasies concerning the power of great art as romantic. Geraghty notes that imagination is central to Baudelaire’s definition of Romanticism, and “is prominent in the film as Tár imagines herself becoming a great symphony composer and viewers also imagine what it would have been like if she hadn’t” transgressed. Tran argues that “Romantic artists, according to Baudelaire, seek to express their own emotions and experiences, which emphasize the artists’ individualism and imagination. I see the movie as Todd Field’s expression of his imagination, emotions, and experience.” It may be true that Field infuses the story with his own imagination and experiences, but they’re not necessarily equivalent to his character’s. Brandon Taylor, a contemporary writer interested in the spiritual efficacy of art in the twenty-first century, recently argued that the conflation of creator and character is one of the primary critical challenges of our moment.9 In this, I agree with Apodaca and Tinaro that while Lydia Tár is a romantic, the film is not.

Figure 8. Rafa Sales Ross (@rafiews), “You’ve na’vi seen a conductor like this,” digital photomontage tweeted September 25, 2022. Ross, a film critic, creates a portmanteau of two popular films playing on the romantic exoticism of Tár’s anthropological research into Indigenous Peruvian music and the similar “Noble Savage” discourse present in Avatar (dir. James Cameron, 2009).

As the memes illustrating this essay demonstrate, there’s much more to say about Tár and its impact (fig. 8). Perhaps the question should not be whether the movie is romantic, but how it suggests we should feel about the central character’s romanticism. To Tinaro, “The way the film feels about her music is very romantic. Her nostalgic tapes of Leonard Bernstein conducting speak of music as a secret language and even say that the meaning of the music is an indescribable feeling…. When Tár is talking about her interpretation of Mahler with an audience member, she describes her performance like this: ‘I chose love.’ She can easily choose love for her art, and yet choosing to do the loving thing in her personal life is impossible for her. It seems that Tár’s way of feeling is only that–feeling without action, an incomplete kind of love. Maybe it is also an incomplete kind of music, the movie’s creators seem to suggest, for she never seems to finish her newest composition.”

Indeed, and I might argue that she practices an incomplete, fragmentary kind of romanticism by failing to achieve the real success of the movement: exposing the emotional dimensions of spirituality, politics, violence, and the everyday. Great art moves the creator and receiver, inspiring the soaring suspension of time that Lydia Tár so loves, but it also can—and some Romantic artists argued should—be urgently invested in the now.

Tár carefully shapes the monolith that is her work and leaves everything else in pieces. Consequently, her relationships with family, community, and colleagues, her physical, mental, and spiritual health, and, in the end, her personal and professional lives become dangerous fragments. The sharp edges of Tár’s romanticism cut and weaken her until the central project—her musical career—loses its form too. Ultimately, I’m left wondering whether Tár’s artistic capacity emerged from her selfishness or despite it.

While it’s not precisely capital-R Romantic, the film does offer the opportunity to explore the essential human questions that captivated historical Romanticism. All the better that it leaves these questions unanswered because, as Tár expounds in a pivotal scene, “It’s always the question that involves the listener.”

Charles Baudelaire, The Salon of 1846, introduction Michael Fried, (New York: David Zwirner Books, 2021).

Robert Rosenblum, Modern Painting and the Northern Romantic Tradition: Friedrich to Rothko (New York, Evanston, San Francisco, and London: Harper & Row, 1975).

I have lightly edited student responses for clarity.

Thomas McFarland, “Romanticism and the Form of Ruins,” in Fragmented Modalities and the Criteria of Romanticism (1981; Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014): 3-55.

William Calder, “Behind the Mask of Agamemnon: Is the Mask a Hoax?” Archaeology 52, no. 4 (July-August 1999), unpag.

The philosopher Edmund Burke describes this feeling of awe in the face of the vastness of the universe in philosophical and religious terms as the sublime.

See Matthias Hayek, “Correlating Time Within One’s Hand: The Use of Temporal Variables in Early Modern Japanese ‘Chronomancy’ Techniques,” in Coping with the Future: Theories and Practices of Divination in East Asia (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2018): 530-558.

These paintings are held by the Museo del Prado in Madrid, and the scholarship on them is vast. See the museum’s website for an introduction.

On this idea and Taylor’s literary exploration of the spiritual efficacy of art and aesthetics, see Taylor’s recent novel, The Late Americans (New York: Riverhead Books, 2023); his vast scholarship on Twitter and Substack (@blgtylr); Brandon Taylor and Adam Dalva, “Brandon Taylor: ‘The story can’t be so loyal to one character that it betrays another’,” Guernica Magazine (June 5, 2023); and Anthony Domestico, “Too Late for Grace? Brandon Taylor’s Novel of Finish and Style,” Commonweal Magazine (June 6, 2023).