Nature Morte (sort of): a farmer’s meditations on still life

Emily Shapiro

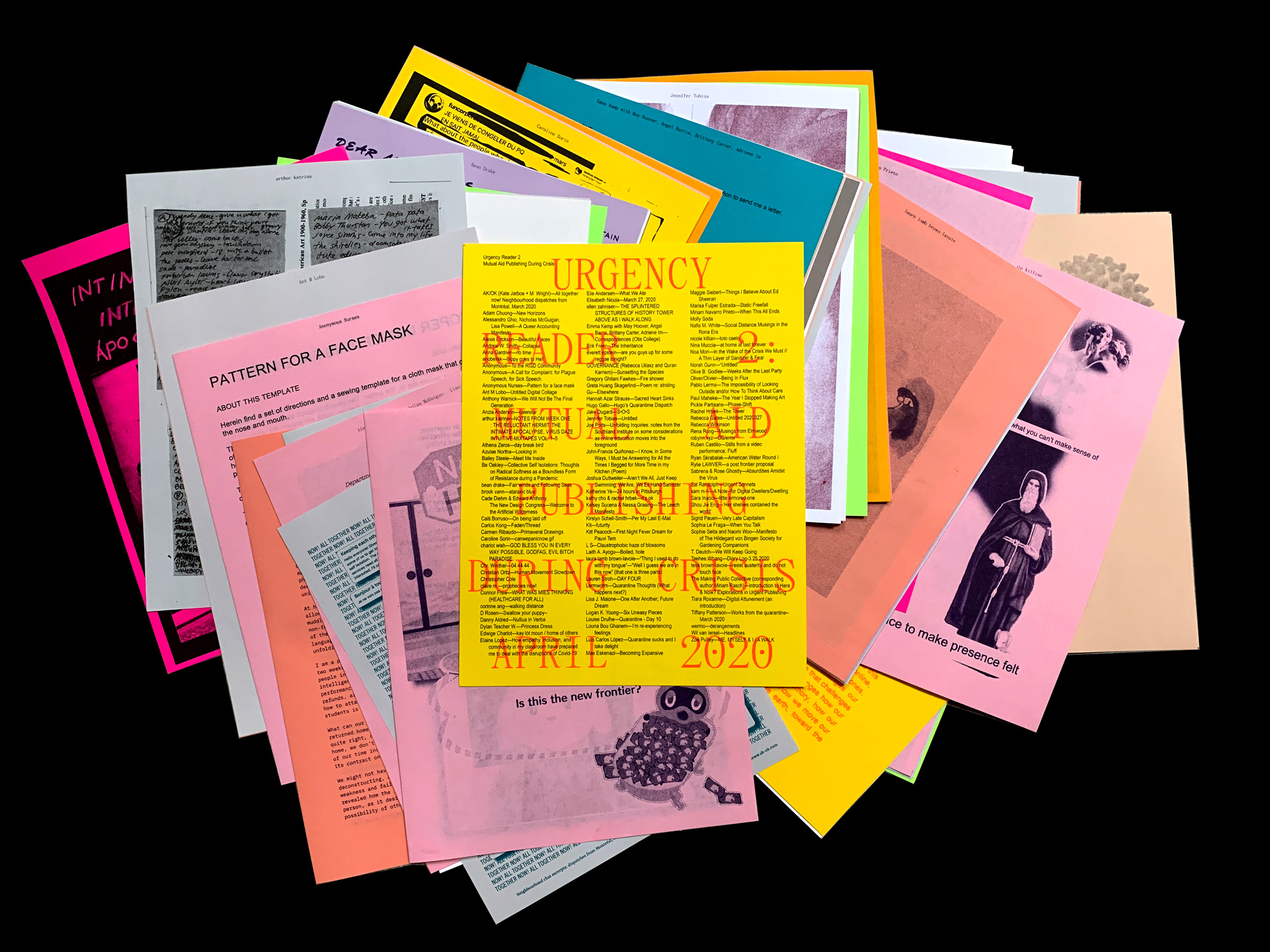

Amy Beecher Beautiful Beautiful Beautiful Rose I and II on view in Nature Morte (Sort Of) presented in PCG's Hunt-Cavanagh Gallery, 2022. Image: Scott Alario

So much of being in and perceiving nature is in the physicality of it; we experience nature with all our senses. Touched and surrounded by a landscape, a field in flower is as much about the wind and the birds and the gentle earth as it is about a rose. As both an artist and herb and flower farmer, I am acutely aware of the desire to freeze the sensuality of an experience of nature in time, the purported goal of the genre of still life.

But the life of a flower is over the moment you pluck it from the ground, and the attempt to capture the essence of nature in art is in itself a sort of death. No matter how many times I dream of capturing and bottling the essence of those tiny moments in the field each season, I cannot snap a screenshot of the birdsong and my hands stiff with dirt, eyes squinting against the sun and the feel of the grass. Nature is force and elemental life, the feeling of it unable to be explained or depicted, and the Nature Morte genre is an idea and artistic method that seems to understand the presence of death in any attempt to capture the sensuality and ephemerality of nature.

And so I entered Nature Morte (Sort of) with curiosity, eager to be among the flowers again in cold December. In the gallery, of course, it isn’t the force of nature you feel, it is the presence of your own body, memories, and experiences. The nature depicted remains still, silenced and encased in glass and framed by stark white walls, waiting.

Nature Morte (Sort of) in PCG's Hunt-Cavanagh Gallery, 2022. Image: Scott Alario

While a flower will live and grow and move whether or not it is observed, the life of a work of art on a gallery wall exists only insofar as it is witnessed, dissected, or admired. And my own reactions and associations infused the works with meaning and symbolism, forcing out earthliness in favor of the semiotic existence of a rose, a bouquet, a garden. There is a powerful contrast between the earthly, material existence of a flower and what it has come to symbolize – passion, sex, beauty, and grace – and what we see depicted in Nature Morte (Sort of) is not the rose: it is a dead thing, an idea. Detailed and vivid, hypernatural and stark. Nature dead, indeed.

In a garden, even from the first moments of growth, there is death: disturbed mycelia with each hole in the soil; offending grubs unceremoniously squeezed and tossed aside, the slugs eating the broccoli that must be drowned in plastic cups of beer to save the crop. The birds eat worms, the cats hunt mice, a rotting log on the edge of the woods is host to all manner of insects and fungi. In the fullness of June the garden weeps with life, and it is easy to forget death, swaddled in the abundance of fragrant flower petals and the damp lushness of early summer. But there is no beginning nor end: death is ever present, and the garden knows it is dying and prepares itself without melancholy. Seeds emerge from decaying petals that smell so sweet and poignant you want to kiss them it as they wilt. Death is the mother of beauty, and you must trust that a field in flower is willing to die, it must die.

Nature Morte (Sort of) plays with what happens when you place the ephemeral and sensual qualities of plants within the context of an indoor gallery, grappling with the ways in which death can live alongside memory, beauty, and fecundity. The vibrant green and white color-blocked walls convey a sense of sterility and domestication; a bright, tame container where nature can safely be investigated and analyzed. Behind glass, these artworks are frozen, sterile, a sort of deadness unknown in the garden, but no less generative.

Kate Blacklock on view in Nature Morte (Sort Of) presented in PCG's Hunt-Cavanagh Gallery, 2022. Image: Scott Alario

In Nature Morte (Sort of), the artists’ works range from vivid, hypernatural photographs of flowers – Kate Blacklock’s playfully overlayed with a shimmering of slightly uncanny color – to vague, abstract references to nature like the pixelated lines and intricate connections of Antionio Carrau’s Still Life I and II. These complex collages with pixelated lines and geometric renderings resemble genetic code sequencing, the blocky shapes, unpretentious pastel color, and overlapping material elements a kind of bright conflation of memories: lived experience and two-dimensional visual input competing for dominance in the mind.

Edwige Charlot and Daniel Rios Rodriguez’s works infuse something of the holy into their canvases, framing an intricate, multidimensional tree or closely captured natural form with architectural shapes, thus creating a stained glass window into identity and culture past and present. Elizabeth Corkery’s graphic layered cut-outs position portions of a manicured garden as tiers trailing into a dark background. Her installation, which places three framed vignettes that act as gardenscape shadowboxes in front of photo-printed drapes, calls attention to the human attempt to tame nature, and in doing so, reveals just how wrong we get it: the pattern is flat and unnatural, the deep greens computer rendered tones that fall dull and heavy.

Will Hutnick Untitled Coordinates on view in Nature Morte (Sort Of) presented in PCG's Hunt-Cavanagh Gallery, 2022. Image: Scott Alario

The playful abstraction of Will Hutnick’s work is somehow the most alive of the collection. Another Dimension Another Dimension, abstract as it may be, succeeds in capturing something of the frenetic feel of a garden in bloom (dirty knees, bee stings, the joy of a butterfly, the devastation of drought) while simultaneously introducing something new. The work questions the meaning of the word nature, embedding chains, leaves, seaweed, and an unsteady pulsing rhythm of physicality against a bold red backdrop. Hutnick’s work is not simply a still life. It displays a relationship to death that is evolving, like the feel of the garden, like the work of grief. We ingest the plants we grow, dry the herbs and flowers harvested in midsummer, save seeds to plant again, remember our wise dead when they have passed: our relationship to these things does not die when they do. And Hutnick’s work, like most of the artworks on display in Nature Morte (Sort of), resists the impulse to sum things up. The story told through these works is emotionally charged, but often formless, without a clear beginning or end.

In winter, what was once a field in flower is dormant, decaying. The stems of last year’s plants claw bleakly from the ground, surrounded by fallen leaves and weeds left bleached by cold. But this is not a still or unmoving death, it is not an end. When things die in the garden, they find their way into the soil and become part of the ecosystem. Appropriately, Nature Morte (Sort of) reflects an abstracted, ambiguous impression of the place of still life in contemporary art, recycling and reimagining its possibilities. Though never explicitly addressed, the shadow of the climate crisis hovers in the room. The gallery was quiet and empty besides myself when I visited, and the fragments of green leaves and plant matter, stark against the walls of the space, seemed cut from the mind and pasted into the pristine gallery setting, a reminder of the ways in which we have bent and shaped this world to our will. Still, the heart of nature, vivid but ephemeral, shines though. It trails into unknown paths, just as the garden, even neglected, continues to grow.

Learn more about Emily and her work with plants at Night Garden Herbs.