Narrative Interventions: Design Research in Archives and Museum Collections

Writing and Photographs by

Holly Gaboriault

Costume and Textiles Curator Kate Irvin unfurls an early-20th century Scandinavian woven textile. Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design Costume and Textiles Collection. Image courtesy of the Author.

In a society haunted by its past and with a propensity to neglect its histories, we can never learn the innumerable stories within our museum collections and institutional archives. Design research can be viewed as two approaches: one, designers’ attempts to better understand the fundamental needs and challenges of users for a particular object, space, or experience; or two (as applied here), as a method to unearth information from multiple sites regarding a particular artist, designer, object, place or event and ultimately insert that history into public awareness.1 “The archive” encompasses cataloged traces, ideologies and cultural practices, all deemed historical. A place of both fact and fiction, these spaces are largely shaped by what is preserved in parallel to what has vanished, who remains hidden, and who has been erased. What are these critical moments in which certain histories become hidden? What is the function of storytelling in recognizing these absences, and shifting silencing power structures? A project of imagination rather than epistemology, object-based research is a constructive tool for reframing this void in the archive, activating new narratives. I have documented others’ lives and practices for over ten years, and I now consider these hidden histories as a construction site for creative practice. On the museum as a vehicle of elasticity and openness, the Swedish curator, Pontus Hultén stated, “[a] collection isn’t a shelter in which to retreat, it is a source of energy for the curator as much as the visitor.”2 While the very mechanisms that record history have created capacities and systems to select and neglect, artists and designers who conduct research at these sites have the opportunity to intervene from a place where absence is acknowledged, rather than disregarded, and stimulate discovery and discourse.

Engaging archival absence as motivation rather than limitation, artists infiltrate sites of scholarship to expand the margins for dialogue and disruption. In his groundbreaking exhibition Mining the Museum (1992) at the Maryland Historical Society, research-based artist Fred Wilson centered his museological critique composing objects from storage that addressed the neglected Black historical legacies in the persistence of the colonialist lens.3 Wilson’s work exposes and destabilizes the violent foundations upon which such Historical institutions and collections were built, through practices that continue to be accepted. For projects such as Raiding Neptune’s Vault: A Voyage to the Bottom of the Canals and Lagoon of Venice (1997–98) and Cabinet of Extinction (2022), artist Mark Dion crisscrosses archaeological excavation, environmental advocacy, and systems of exhibition in his multimedia installations that inspect standardized methods of gathering, ordering, and displaying in museum spaces. Dion’s approach reveals how institutional collections were often constructed by accident, with varying applications of censorship, facilitating collection-based excavations that question hierarchies and allow unexpected conversations to flourish between items on display. Such creative thinkers and artists operate as detectives, behavioral scientists, journalists, codebreakers, mediators, and activists

Exhibition view of Katarina Burin’s Authorship, Architecture, Anonymity: The Impossible Career of Petra Andrejova-Molnàr, ICA Boston, 2013. Image courtesy of the Author.

As the 2014–15 Getty Research Institute artist-in-residence, artist and filmmaker Tacita Dean continued her practice of utilizing archiving as an artistic tool to explore chance encounters with objects in her project “The Importance of Objective Chance as a Tool of Research”. In the Getty Special Collections, Dean’s strategy was to start with the idea of not having an idea, to conduct her own unconscious search in a location where searching is the primary intention. A journey in unsystematic and indiscriminate accumulation, caught up in moments of finding fragments. Dean selected objects off shelves at random from numerous individual archives constructing a limited edition of bespoke exhibition boxes titled Monet Hates Me, each containing fifty objects generated through a scholarly game of chance. Theaster Gates has incorporated rescue into his practice, saving the record collections of Olympian Jesse Owens and the pioneering house music DJ Frankie Knuckles. Gates first exhibited Black Image Corporation in 2019 at the Fondazione Prada, a curatorial installation incorporating the archives of the Black-owned Chicago-based Johnson Publishing Company (JPC), whose magazines offered a contemporary panorama of Black identity and the African American experience. Framed images by staff photographers Moneta Sleet Jr. and Isaac Sutton hung above visitors browsing through original copies of Ebony and Jet magazines amidst the original furnishings designed for JPC’s offices.

Biography is another vehicle to question narrative authority and lean into the untold. In collaboration with filmmaker Cheryl Dunye, artist Zoe Leonard produced The Fae Richards Photo Archive (1993-96), comprised of eighty-two images that document the life story of an imaginary person: a black lesbian actress and blues singer named Fae Richards, in response to archival absences and black obscurity. The production of the archive can underline the desire for traces of a fictionalized figure in the moments deemed worthy of remembrance. This manner of creative Black semi-nonfiction is explored by Saidiya Hartman’s in her 2008 essay “Venus in Two Acts”, in which she coined the term critical fabulation, the act of recovering the suppressed identities of the past through radical imagination. Authorship, Architecture, Anonymity: The Impossible Career of Petra Andrejova- Molnàr (2008-2018), was the first comprehensive retrospective exhibition featuring an eighty-year-old archive of a successful interwar female Czech designer consisting of architectural drawings and scale models, handcrafted furniture, ceramics, and documentative photographs. Regardless of the evidence presented, Andrejova- Molnàr is a fictitious creation, a decade-long effort by Katarina Burin intended to undermine the typically patriarchal canon of design history. Burin conjures the archive as a result of examining multiple interwar archives where images of Modernist architecture were dominated by male architects and women are positioned in the photographic frame as figural decoration dwelling in the male genius. Driven by the conspicuous omissions of women, Burin manufactured one woman’s identity who, if given the chance, would have existed.

Japanese Katabira (unlined Summer kosode), c. Late-1700s. Maker unknown. Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design Costume and Textiles Collection. Image courtesy of the Author.

Archives, including those who administer and oversee them, confirm authority and set rules for its credibility, which results in the selection of the stories assessed as significant. The closets, drawers, and boxes of storage become secret chambers containing lived moments waiting to be unpacked. In archival research, one doesn’t always have to know precisely what they are looking for, leaving the opportunity for happenstance discoveries. While researching in the Rhode Island Historical Society costume collection closet, I accidentally located two dresses with fringed sleeves wedged in the embrace of Nineteenth-century taffeta and velveteen dresses. What I would soon acquaint myself with was the Camp Fire Girls archive. Founded in 1910, a precursor to the Girl Scouts, the Camp Fire Girls intended to educate adolescent and teenage girls from an amalgamation of patriotism, Catholicism and the “ways of the American Indian” in the seasonal campsite setting. Through appropriated imagery and costumed performance, the Camp Fire Girls is a product of the white fantasy of Indigenous histories, without actually engaging local native communities.3

Camp Fire Girls Dresses, c. 1910-1920s. Maker unknown. Costume and Textile Collection Closet, John Brown House, Rhode Island Historical Society. 2020. Image courtesy of the Author.

From the 1910s into the 1970s, members wore handmade brown suede dresses with strands of colored wooden ‘honor’ beads, each color bearing its own attributes to a specific goal or task accomplished. Hand-painted detailing and dress patches made of fictional ‘indigenous’ pictograms correspond to books filled with this imagined cosmology embodying the Camp Fire Law: Worship God. Seek beauty. Give service. Pursue knowledge. Be trustworthy. Hold onto health. Glorify work. Be happy. Discovering the Camp Fire Girls archive was merely the tip of an expansive and necessary conversation about settler colonialism across the United States.4 Material culture, like these dresses, is a manifestation of complex and shifting demographic relationships, and engaging this archive is an opportunity to understand how these relationships have (or haven’t) changed through time. The staff at the RIHS couldn’t understand why I was so eager to investigate, view, and photograph the CampFire Girls archive, but it is a facet of the settler colonialism that permeates so many American collections, redolent with the often unacknowledged ancestral trauma of Indigenous people. Documenting and illuminating this past, explains much about the ongoing consumption of other cultures.

Fashion Designer Leo Narducci showing a look from his 1968 Narducci, Inc. collection. Narducci Archive. 2020. Image courtesy of the Author.

Occasionally the role of researcher transforms into one of archivist, as was the case in my work with the Narducci archive. Filming American fashion designer Leo Narducci for a documentary, I was captivated by his ability to tell spectacular stories with a cohesive visual legacy to match. After graduating from Rhode Island School of Design in 1960, Leo moved to New York City where he quickly made his mark in the fashion world, winning a 1965 Coty Fashion Award and launching his own label. The Narducci archive chronicles one of the most evolutionary chapters in American culture through fashion illustrations, editorial press clippings, correspondence, scrapbooks, and fashion photography. To find such comprehensive documentation of a designer’s career is beyond unique considering how easily archives are lost, destroyed, or simply go undetected for preservation. To have the owner of an archive by your side, providing oral history for each item was a rare privilege. Much like a treasure hunt, archival clues led me from phone interviews to studio visits and fashion archives, mapping an entire constellation of artists and designers who remained undocumented and unfamiliar to most, reflecting a significant history of fashion that has gone unrecognized: from designers living openly queer lives at a time when being gay was criminal, to women chipping away at glass ceilings, to generations of designers achieving success beyond cultural and racial marginalization, so many of whose careers were eclipsed or ended by the AIDS pandemic. The American fashion world is built on ground paved at the cost of its obscured designers and forgotten innovators. The weight of these untold stories feels staggering, and if/when found, such archives elicit both a sense of obligation and determination to make these histories known.

Connie Hicks “Rhode Island Banking Crisis” coat, c. 1991. Costume and Textile Collection Closet, John Brown House, Rhode Island Historical Society. 2020. Courtesy of the author.

Concerning modern artistic practice, curator and historian Glenn Adamson maintained that the contemporary has always been defined by a series of “contingent horizons”, borders that can never be reached but intrinsically exist at the edge of something else. Design research exists on this edge by examining the displacements of these hidden histories and assembling historical relationships to what has been damaged or compromised. Research does not always provide the answers; in many instances it creates more questions. Whose memory is at stake in the archive? Who are its caretakers and what are their roles in stewarding this material? What are the boundaries of gatekeeping? Who exactly is this content being preserved for, especially if it remains concealed and inaccessible? Let us rethink the archival space as a construction site: positioning the history and geographies of objects not as that which has happened, but as that which is continually happening.

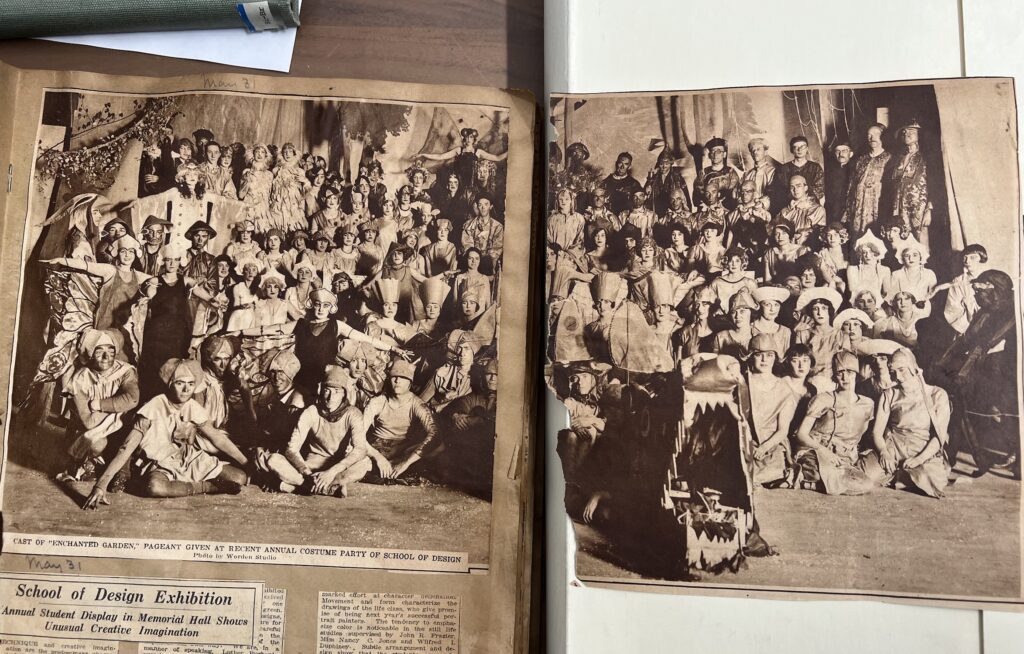

William E. Brigham dressed as the Phoenix, “Cast of ‘Enchanted Garden’ Pagent Given at the Recent Annual Costume Party of School of Design”, Providence Bulletin, May 31, 1923. Special Collections Fleet Library Rhode Island School of Design. 2022. Image courtesy of the Author.

The archive is a space of reduction, extraction and loss, which bears opportunities to reawaken concealed moments and reclaim unheard voices. Opening these chambers to artists and designers for research provides different ways of narrating history in institutional settings. The staging of objects, their interpretation, and the imagination of proposed historical relationships ignite discussions about what is represented and, to a greater extent, what is not. Our notion of archival presence should be infused with the awareness of the absence: often it is the frame that constricts, not the view. Over the years, museums and archives have created more initiatives, artist-in-residence programs, and fellowships for designers to engage with their collections in creative ways. In this way, museums can transform their roles as stewards and gatekeepers of the archive towards a more open strategy that acknowledges voids in the narrative and the stories left behind. Within these spaces, design research of objects and documents becomes an interactive approach that challenges established historical narratives through creative research practices. Design researchers enter into these spaces with a desire to amplify the forgotten beginning with one question: tell me your story.

As Holly points out, design research has expanded as a field beyond the specific of user-object relationship, to an epistemology; in this light design research is about understanding different praxes, or theoretical applications, as examined by Nigel Cross in Designerly Ways of Knowing.

This quote is from Hans Ulrich Olbrist’s 1997 ArtForum interview with Pontus Hultén, entitled The Hang of It.

Click here for a reflection on how “Mining the Museum Changed the World,” by Kerr Houston, 25 years after Wilson’s groundbreaking exhibition.

The exhibition Americans at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian details the long established and ongoing history of the appropriation and use of Indigenous imagery/imagery of Indigenous peoples to bolster an “American” identity, “from the Land O’Lakes butter maiden to the Cleveland Indians’ mascot, and from classic Westerns and cartoons to episodes of Seinfeld and South Park.”

According to the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School, “Settler colonialism can be defined as a system of oppression based on genocide and colonialism, that aims to displace a population of a nation (oftentimes indigenous people) and replace it with a new settler population.”