Cammie Staros: Unearthing the Sky

Exhibition Review by

Michael Zhang

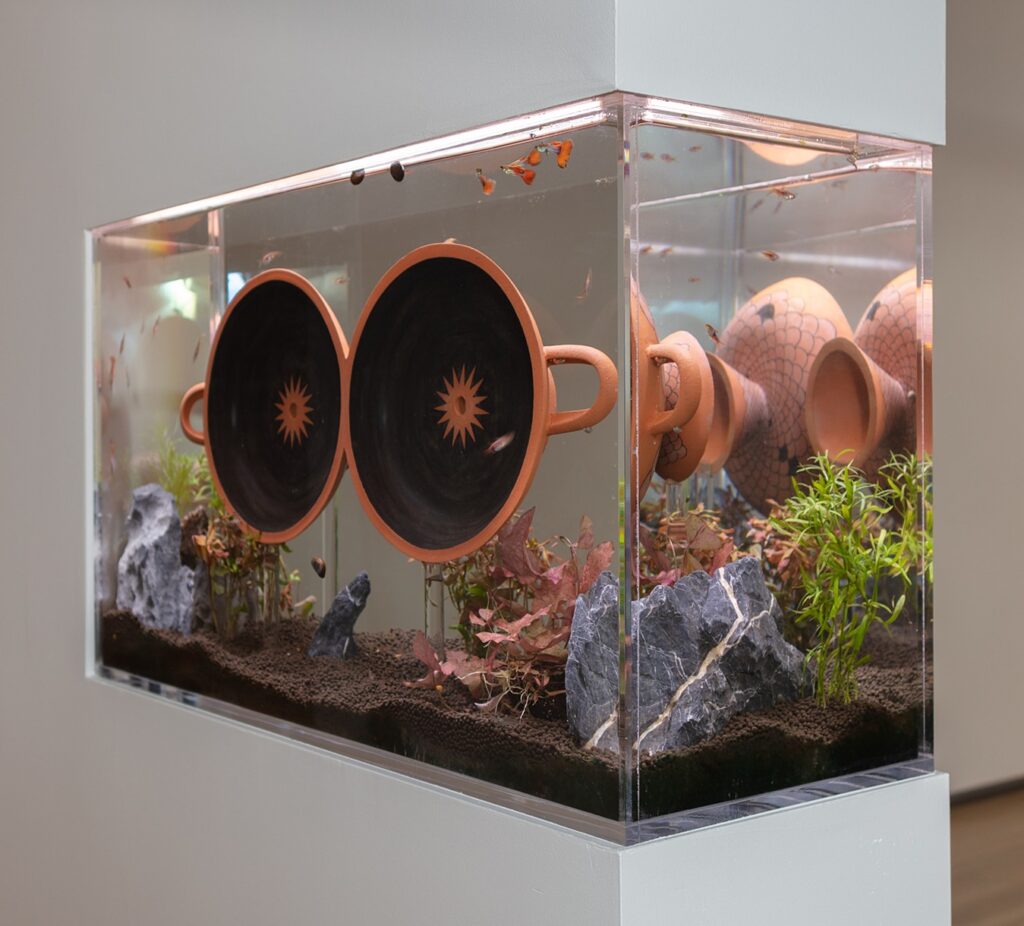

Cammie Staros, Figlinum aquaticum, 2021. Ceramic, acrylic, wood, laminate, water, aquatic filtration system, programmed grow light, river rock (pebbles), Volcanic Rock, Honeycomb Rock, Zebra Stone

Curated by Kate McNamara, former PCG Interim Director (2022)

Reilly Gallery at the Smith Center for the Arts, Providence College Galleries

November 1, 2023 to March 2, 2024

Unearthing the Sky, an exhibition organized by Providence College Galleries, presents a series of sculptural works by the artist Cammie Staros (b. 1983). The exhibition marks a homecoming to Providence for Staros, where she earned a bachelor’s degree from Brown University in 2006. Staros currently lives and works in California, where she earned a MFA from the California Institute of the Arts in 2011.

Several sculptures from Staros’ portfolio were arranged throughout the space of Reilly Gallery, cohesively tied together by the concept of time as a central theme. Across her work, Staros investigates the legacies of the past and the conditions of the present, while meditating upon the future. Staros’ sculptures directly engage with pottery from Classical antiquity and their historic contexts, while also incorporating formal elements from modern sculpture. Staros traces the lineage of sculpture back to Greco-Roman art as the point of origin of the Western canon. She does so in examination of the ways that the Classical period has influenced the development of Western art history and shaped contemporary artistic practices.

Staros uses terracotta and clay as the material basis of her sculptures, reflecting the composition of Greco-Roman pottery. In addition, Staros incorporates materials like stone, neon lights and marble to examine the role of materiality in wider social and art historical contexts. The artist also experiments with the formal elements of her sculpture, drawing from the ethos of modern art. In doing so, Staros bridges Classical and modern sculptural practices.

Cammie Staros Old Ocean, 2018 Neon and walnut

In Old Ocean (2018), neon light tubes coil around two sculpted walnut arms that extend perpendicularly from the gallery wall. The protruding arms conceptually engage with the presentation of Classical sculptures, many of which are missing noses, limbs, or other body parts, within the context of the museum. But what is missing in Old Ocean is the body itself. This results not only in a material absence but also a contextual loss.

By entwining the arms with neon light, Staros endows the piece with a more contemporary resonance. Neon had a captivating allure that led to its widespread commercial adoption in the late-twentieth century. It was commonly used in advertising displays and storefront signs. It also piqued the interest of modern artists, who explored the social and capitalist implications of the medium, as well as its fluorescent visual properties.1

Through her choice of materials, Staros investigates both the development of art as a field, as well as the making and remaking of narratives. In her piece from 2015, Siren (Rousseau), Staros presents a pottery work featuring elongated handles reminiscent of ears, and a long stem that delicately and precariously balances on top of a slender brass rod. The brass rod evokes a visual association with Constantin Brancusi, whose signature brass sculptures channeled the energy and speed of the modern world.2The artwork’s title makes reference to the self-taught French artist Henri Rousseau, known for his so-called “Naïve” mode of painting characterized by a simplistic, folksy style.3 Once again, Staros bridges the realms of antiquity and modernism, but she does so in a way that reveals, despite modern art’s self-proclaimed break with the past, the legacies of Greco-Roman art continue to exert a significant influence on contemporary art.

Antropos (2018) perhaps refers to the oldest of the Three Fates, and the figure who wielded the power to cut the thread of life, Atropos. Staros’ sculptural work draws inspiration from depictions of armored breastplates on Greek urns, but also incorporates aesthetic elements derived from Primitivism, Minimalism, and other modernist art schools. However, given the titular theme of the work, I would have liked to see Staros push more against the conceptual and chronological boundaries of art. Just as Atropos severed the thread of life, there was room here for the artist to explore a more radical break by severing not only the thread that connects the Classical period to modernism, but also raise critical questions about modern art’s legacies and impact on contemporary and future artistic developments.

Across her work, Staros also engages with the concept of identity. In How Neat the Fold of Time (2017), the artist presents an earthenware vessel adorned with a pattern suggestive of a Greco-Roman dress. Staros examines the portrayals of women in Classical pottery paintings and reflects on the representation of gender roles across time and place. My Soliloquy to Your Chorus (2017) is a sculptural piece resembling a head, adorned with several brass rings that allude to ear and nose piercings. Painted in black, it is devoid of any facial features. Reduced to anonymity, the piece evokes an anxiety over the fading of memories and the loss of identity over time.

The Weight of Medusa’s Head (2017) depicts a rust-colored steel pipe penetrating an earthenware vessel painted with the coiled snakes comprising Medusa’s hair. The formal aspects of the piece also directly refers to a pair of sculptural columns found in the Basilica Cistern in Istanbul, Türkiye.4 In the cistern, the base of each column depicts Medusa’s head upside down, being crushed by the weight of the pillars above. On Staros’ vessel, the artist painted a single eye, symbolizing Medusa’s terrifying power. Wide open and alert, the eye’s unwavering gaze confronts every viewer who encounters it.5 This piece raises questions about the concept of female agency throughout Western history, and prompts viewers to reflect on Medusa as a victim of a social structure that seeks to repress the agency of powerful women.

Cammie Staros, Figlinum aquaticum, 2021

Figlinum aquaticum (2021) is arguably Staros’ most effective work in the exhibition. It was certainly her most popular work, as it was the center of attention among the opening night audience. The installation comprises two replica Greek wine cups submerged in an aquarium. The vessels were part of a composition that also included rocks and plants, now home to small, brightly colored fish. The submerged Greek cups allude to the underwater archaeological discoveries of objects from antiquity. Time and decay have sunk the remnants of an ancient civilization to the bottom of the sea. Juxtaposing an underwater ecosystem with the decline of ancient human civilizations, Staros also draws our attention to the present and impending crisis linked to climate change.

The element of time occupies a central position in Staros’ work, often being a source of significant tension. In Figlinum aquaticum, human time and geological time are at odds. Humanity strives to safeguard the remnants of past civilizations, while also seeking new ways of creative expression. But when viewed through the lens of geological time, these efforts appear futile. On a geological time scale, traces of human civilization are a mere blip on the timeline. Nature will quickly reclaim the geographies that we occupied with complete indifference to humanity’s bygone presence.

Cammie Staros Testa conchea, 2022 Ceramic, powder-coated steel, pink marble

The formal arrangement of Testa Conchea (2022), in which a pink marble orb is connected to a warped terracotta amphora by a curved black rod, evokes the outline of an ammonite shell. Like Figlinum aquaticum, the installation suggests the passage of time on both human and geological scales, as the pottery and outline of the shell serve as signs of the decay afflicted by time on both evolutionary development and human civilization.

Through her work, Staros conducts a comprehensive examination of the influences and legacies of Greco-Roman art on Western artistic development. If the legacies of Classical art are Staros’ field of inquiry, modernist sculpture is the vehicle through which she conducts her critique. However, there were opportunities for the artist to disrupt the canon in a more radical way. Modern sculpture in the twentieth century did indeed mark a pivotal break from previous traditions, as artists dismantled prevailing paradigms and searched for new forms of creative expression in a reassessment of humanity in the wake of devastation between and after the world wars. But modernism is becoming a historical period in its own right, as we move further from its origin. Furthermore, at the present moment, modern sculpture is no longer perceived as a radical break from a previous lineage of humanity; modernism itself has attained canonical status in art history.

Additionally, modernist sculpture as a field was founded and developed by white male artists, much like the arts of the Classical period. Staros had an opportunity to chip away and challenge this patriarchal structure by referencing the contribution of women artists, artists of color, and non-Western artists in lieu of Brancusi’s brass sculptures, the geometric abstraction associated with Primitivism (a school of art that owes a profound debt to the arts of Africa and Oceania),6 and Dan Flavin’s neon sculptural pieces to trouble the archetype of the white male genius in Western art history.7 In other words, Staros could have inquired more deeply and more critically into the problems of modernism alongside her engagement with antiquity.

In closing, Cammie Staros: Unearthing the Sky is an ambitious exhibition that critically examines the influences of Classical art on contemporary Western art history and artistic practices. The exhibition is visually captivating, as Staros’s experimental sculptural forms introduce new ways of looking at and interpreting Classical pottery. Staros overlays multiple levels of meaning in her work, effectively bringing together an interdisciplinary mode of inquiry that bridges archaeology, ecology, and economics. Staros also engages with pressing contemporary issues, such as climate change and identity politics. While the show raises more questions than it provides answers, this is also an accurate and truthful reflection of how none of us currently possess the solutions to humanity’s ongoing crises.

See examples of neon art in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art.

An example of this is Constantin Brancusi’s sculpture, Bird in Space. An edition of this work, executed in 1924, is in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

See Henri Rousseau’s page at the Museum of Modern Art for a biography of the artist and a list of selected artworks.

To read more about these columns, see Michele Lent Hirsch article in the Smithsonian Magazine.

During the Artist Conversation hosted by Providence College Galleries on November 1, 2023, Staros mentioned that the first time this piece was exhibited, it was placed facing a corner. In this exhibition, a curatorial decision was made to direct the eye’s gaze towards the audience.

For a brief overview of the ways that African art influenced European modern art in the twentieth century, see Denise Murrell’s essay published by The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

See Dan Flavin’s page at the Guggenheim for the artist’s biography and a list of selected artworks.