Cabinet of Curiosities

Cabinet of Curiosities

Ruane Center for the Humanities

Program Description

Beginning in Europe during the Renaissance, cabinets of curiosity, or wunderkammers, were created to showcase manmade and natural treasures from around the world. In the Age of Exploration, eager collectors could impress visitors with objects from newly conquered lands, as well as works of great artistic craftsmanship and instruments of scientific importance.

This interpretation of a cabinet of curiosity combines contemporary artworks by California-based artist Rob Andrade with older works from Providence College’s campus collection and a specially commissioned wallpaper by Rhode Island-based artist Kirstin Lamb. Lamb, whose series of four paintings After French Decoration can be seen across the hallway, has previously made work dealing with cabinets of curiosity. For this wallpaper, PCG commissioned Lamb to create a digital drawing of our collection objects, which was then printed onto vinyl and attached to the back of the cabinet. Andrade’s sculptures are based on themes from the Development of Western Civilization curriculum, and include references to monuments, artifacts, and rituals from throughout human history. Some of these include representations of the Venus of Willendorf, ancient Egyptian cat statuettes, and Akua Ba fertility figures. Many of these works are 3D-printed, or combine 3D printing with other found objects and industrial materials. Andrade also created various platforms and vessels to aid in the display and viewing of some of his creations. Objects from the college’s Campus Collection include medieval reliquaries, portrait busts, and a 16th-century enamel triptych. Many of these objects were donated to Providence College in the early 1960s by Thomas F. Flannery Jr., a collector of medieval art. Others are reproductions of artworks which have been collected and used for teaching purposes.

Image Gallery

-

On the center shelf of the rightmost cabinet, lying on a block of wood, is a 3D printed figurine of the Cycladic Venus. The Cycladic culture, which flourished in the islands of the Aegean Sea between c.3300-1100 BCE, was best known for their artworks of marble figurines, most commonly single full-length female figures with folded arms across their fronts. These figures usually had a sharply-defined nose but smooth blank faces, although there is some evidence that the faces were originally painted. https://cycladic.gr/en/page/kikladiki-techni -

In ancient Egypt, the cat was a highly esteemed animal with close links to women, and was often depicted as an important member of prominent households. Between 664-332 BCE a cult evolved around the cat goddess Bastet, who embodied the fierceness and power of a lion tempered by the grace and affection of a cat. In many tomb scenes cats frequently appear seated beneath the chairs of their owners or on sporting boats in the marshes of the Nile River. -

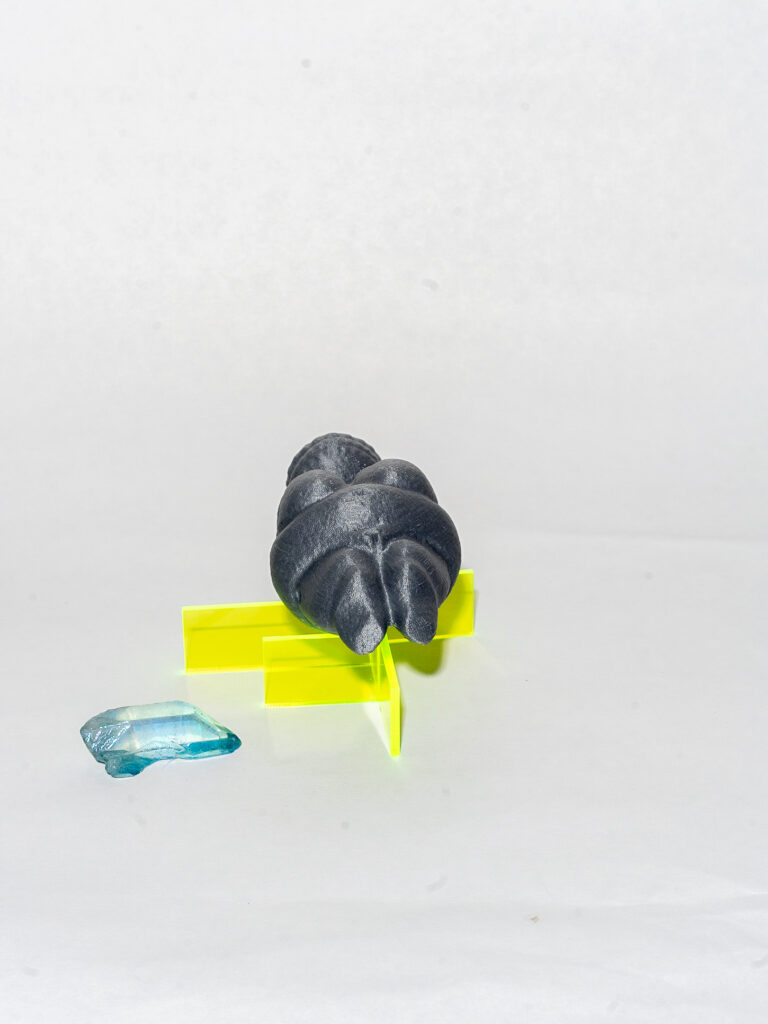

The scarab beetle was a popular motif in ancient Egypt, often used on amulets and impression seals. They were produced in vast numbers for many centuries, and were typically carved from stone or molded from faience, a glazed earthenware process creating a shiny blue-green appearance. These scarabs were generally intended to be worn or carried by the living, and the base was usually inscribed with designs or hieroglyphics. -

The original Venus of Willendorf figurine, now located in the National History Museum of Vienna, is estimated to have been made 25,000-30,000 years ago, although very little is known about its origin, method of creation, or cultural significance. It was found by a workman named Johann Veran in 1908 during excavations at a Paleolithic site near Willendorf, a village in Lower Austria. Many similar sculptures discovered in the 19th and early 20th centuries are traditionally referred to in archaeology as “Venus figurines”, due to the widely-held belief that depictions of nude women with exaggerated sexual features represented an early fertility deity. Yet this reference to the specific goddess Venus is metaphorical, as the figurines predate that myth by many thousands of years. This figure has no visible face, and her head is covered with circular horizontal bands of what may be rows of plaited hair, or perhaps a type of headdress. -

These disk-headed Akua ba fertility figures are one of the most recognizable forms in African art. The Akan people of present-day Ghana idealized a high oval forehead, and the rings around the necks of the figures are a standard convention for rolls of fat, a sign of beauty, health, and prosperity in Akan culture. Most Akua ba figures have abstracted horizontal arms and a cylindrical torso ending in a base rather than human legs. The flattened shape of the figures served the practical purpose for women carrying them against their backs wrapped up in cloth, in the same manner as a mother might carry an infant. This practice originates from an Akan legend of a barren woman named Akua, who carried a small carving of a child on her back and cared for it as if it were her child, only to eventually conceive and give birth to a daughter. More recently, Akua ba figures have become marketable tourist items and are often depicted in jewelry, greeting cards, print ads, and mass media. -

The pylon, or the monumental gate of an Egyptian temple, typically consists of two pyramidal towers, each tapered and surmounted by a cornice and joined by a less elevated section enclosing the entrance between them. As it was the public face of a building, pylons were often decorated with scenes emphasizing a king’s authority. Andrade’s interpretation of the pylon includes faint carvings of hieroglyphics and Egyptian figures which can be seen on the front. -

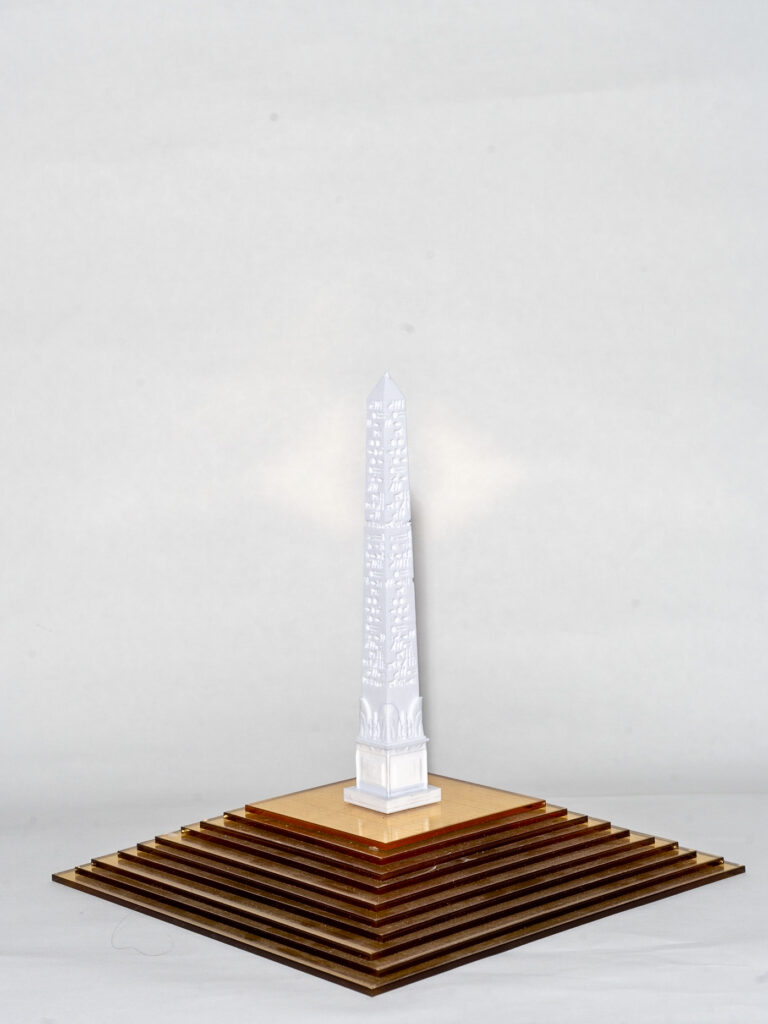

Obelisks, originally called tekhenu by ancient Egyptians, were prominent in ancient Egyptian architecture and played a vital role in religion, often placed at the entrance of temples. In Egyptian mythology, the obelisk symbolized the sun god Ra. Around 30 BCE, when Rome seized control of Egypt, they looted various temple complexes, removing the obelisks and shipping them all over the world. Other cultures, including Assyria and Axumite (present-day Ethiopia), also constructed obelisks, and they have also been replicated around the world in modern times. -

Many Shinto shrines in Japan use elements of white sand in their gardens, which is intended to purify the grounds and make them hospitable to the kami, or spirits. The Kamigamo shrine, an important shrine on the banks of the Kamo River in north Kyoto, is one of the oldest Shinto shrines in Japan. This shrine is dedicated to the kami of thunder, and includes two mounds of white sand in the form of cones, known as Tatesuna and Saiden, whose arrangement signifies the kami descending to the ground in the form of thunder. -

On the top shelf in the center cabinet sits a reliquary from the 14th century. Decorated with architectural panels and spires, the faces of each side are engraved, one end with a figure of Madonna, and the other with God and the crucified Christ. The other reliquary, on the bottom left, is from the 15th century in Northern France, and simulates the design of a Gothic cathedral, and is decorated with two kneeling angels just below the rock crystal compartment. Christian belief in relics, or the physical remains of a holy site or a holy person, dates to the beginnings of the faith itself. Since these objects were considered extremely valuable and precious, it is only appropriate that they were enshrined in reliquaries crafted from precious stones and metals. -

This 16th-century French triptych, or picture divided into three panels, depicts the figure of Christ bearing marks of the flagellation. He is flanked on either side by the Virgin Mary and Mary Magdalene, while in the left and right panels two saints are represented. -

A ciborium is a vessel, normally metal, which held the host before and after the Eucharist. This octagonal-shaped ciborium, made of silver and enamel, is decorated with figures of eight Apostles around the sides and four additional Apostles on the dome-shaped top.